The Mother of all Tumors

Daphne Beal

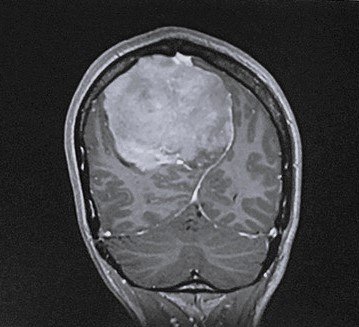

Author’s brain before surgery

Word Count 2193

Seven years ago, a neurosurgeon removed a giant tumor from my head. Near the top of my head on the right and a little to the back, it was in the posterior right parietal lobe and crossed over the midline into the left hemisphere. It was benign—excellent—but it was bigger than a tennis ball (7x8x9 cm) and was making my brain swell, a lot, inside its bony confines. The tumor was so large that after the operation random neurosurgeons would drop by my hospital room to see me, as if I were a sideshow freak. “We didn’t know how you were still alive when we saw the images,” the head of the neurosurgical ICU told me.

Meningiomas grow slowly in the meninges, the three protective layers of the brain, which are about a millimeter thick and poetically named the dura mater, the arachnoid mater, and the pia mater—or the tough mother, the spider mother, and the gentle mother. My meningioma was maybe as old as I was. Parts of it were calcified. I’d had headaches since I was teenager, treatable with ibuprofen, until I woke up one summer night in 2017, howling, feeling as if a helmet was tightening all around my skull. Seven days later, in an eight-hour craniotomy—a word that feels 19th-century—the tumor was removed. A “gross total resection” meant my surgeon (I’ll call him Caleb) cut the whole fucker out. I asked his nurse practitioner, Jen, to describe the procedure.

“Do you want me to be graphic?” she asked. I did.

In the OR, my hospital garb was cut off. I was turned over like a rotisserie chicken, my head in a kind of vice, and the tumor was located from the outside with a “brain GPS.” A large, c-shaped piece of skin was folded back. Six burr holes were drilled and then the dots connected by a saw designed to only go as deep as the bone. The hatch (my word) was removed, the meninges were sliced, “like a rip in jeans,” Jen, with her cool sartorial style, told me. The tumor was “debulked”—removed from the center first—and then from the sides. “It was like taking golf ball out of Jell-O,” she said. Although, she clarified, the yellow-gray mass had the rubbery heft of a lacrosse ball. Finally: two sets of sutures stitched into the meninges; the hatch replaced; Burr hole covers (looking like metal snowflakes) secured by titanium screws, and the skin sewn up. I can feel the ridged topography of the hatch when I touch my head, and thinking about it produces an itchy, dull ache.

Mine was and is a happily-ever-after story. Friends and family flew to my side, advocated in the hospital, took notes, consulted with each other on a back-channel group chat, cared for my children, and fed me delicious things. The outcome was so good I wrote an essay for Vogue. Mine was an aspirational brain tumor. In fact, when I tell people I had a meningioma, those who know them often say “That’s the best kind of brain tumor!” as if I’d gotten a labradoodle.

They aren’t wrong. However, having walked up to the maw of death and stared down its ugly throat before being able to turn around and walk away, I find my relationship to my brain changed—that repository of self, memories, perceptions, emotions, opinions, and physical sensations, too. I talk to the aggregate of 100 billion neurons in my head, or I use some of those 100 billion neurons to talk to the others.

Neuroplasticity is real and miraculous. In the years after the surgery, I felt lighter and brighter than I had a decade before. Tumors are parasitic bloodsuckers and literally exhausting. Without the evil stowaway, to what degree would I have been a more patient and energetic mother, wife, friend, writer? The tumor had pushed the midline of my brain, the falx, out into a giant curve. Soon, the falx straightened out, and the two hemispheres of my personal globe became tidily parallel again, leaving a small space where the tumor had been.

Then, about six months after the operation, I got up after dinner at a barbecue place in Brooklyn and realized my left leg was offline. The circuitry between brain and leg had shorted out. I looked down at my thigh, grateful for the darkly lit restaurant. “OK, left leg,” I instructed silently. “You’re going to do just what the right leg did, up and over. Then we’re going to stand up.” Using both my hands to hoist my leg clear of the bench, my leg and I stood up. “Now, the right leg is going to take a step toward the exit, and you will follow. If things aren’t copacetic by the time we reach the door, we’ll take an Uber.” Fifty feet later, my leg was back online. Problem solved. A month after that, I was teaching when I had the repeated urge to turn my head to the left and fling my left arm out. “Don’t do that,” I told myself. “Your students will think you are crazy.”

When I called Jen, she seemed unsurprised. “Meningiomas are very seizuriffic.” Say what? That word is messed up. Almost twenty percent of people who’ve had meningiomas removed have seizures afterward. And thirty percent beforehand, I learned from my new neurologist, Sophie, and described episodes from the few years before the surgery. The worst one occurred a year earlier as I was walking to pick up my son from camp in downtown Manhattan. Overcome by a kind of vertigo, I looked at a fire hydrant that I knew was a few feet away but seemed to be down a long tunnel twenty-five feet off. My limbs felt noodly, but my insides felt speeded up. I called a friend, and by the time she arrived, I was fine, if shaken. Her doctor friend said it sounded like an ocular migraine. Episodes, milder than these, would happen like mini acid trips as I stared across the table at a friend who appeared far away. Whoa, that’s weird, I’d think, ascribing them to flushes of hormones. (I come from people who are non-alarmist in the extreme if that wasn’t clear already.)

Sophie smiled, appreciating the vivid description, and asked if I’d ever heard of a 45-second migraine. On a scale from 0 to 10, she rated the severity of my seizures at a .1, and said they were called focal aware seizures. I don’t lose consciousness or total control of my body, but until we figured out the dosage a few months later, these seizures came every few weeks with sharp warning spasms under my left ribs that no one else could see. The seizures only affected my left side, as if there were a Sharpie line drawn down my center. Medication quells them, even as a faint outline of their existence lingers in the side-view mirror.

Then I noticed a few years ago, despite my brain being “perfect” (Caleb’s word and I liked it), there were issues that existed before the tumor that had never completely disappeared: my terrible handwriting, with missing or misused words; transposed numbers; and most shamefully, trouble reading, nonfiction and online in particular

Caleb and Sophie both suggested I meet with James, a psychologist in their neurology department, the only place in any hospital anywhere that I actually want to visit. In my first session, James—who has a boyish face and an old soul—told me my brain was still recovering.

“Really?” I asked. “I thought it did that a long time ago.”

“Your brain will always be recovering.” I felt simultaneously hopeful and worried.

James gave me a series of casual tests, some more challenging than others, and then pulled up a map of North America and asked me where Mexico and Canada are. Done. As I opened the door of his office to leave, he asked, “Do you confuse right and left?”

I laughed. “Oh my god, yes! Like twenty times a day.”

Something about the way he asked made me get on the internet, which I rarely do with medical symptoms. The potential for catastrophizing is too great. But within about five minutes I stumbled onto Gerstmann syndrome, which an NIH article describes as “a rare neurological disorder…with a tetrad of symptoms which include impairment in performing calculations (acalculia), discriminating their own fingers (finger agnosia), writing by hands (agraphia) and impairment of distinguishing left from right (left-right disorientation).” I have never had finger agnosia. The syndrome is associated with the parietal lobe, and specifically with a part called the angular gyrus, which is connected to language and number processing, and memory and reasoning. Jesus, how to make a person freak out. I won’t even talk about the Oliver Sacks article.

At my next session James confirmed my research. “You have a very mild version of it. People who have it badly, when they look at the map of North America, put Mexico in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.”

“Will it get worse?”

“No.” I decided to ignore the Sacks article and told a friend I was renegotiating my contract with my angular gyrus. James and I started with logic grid puzzles. At home, I crossed out every second A in newspaper articles and watched TED talks simultaneously, going back and forth between them, taking notes. In one session, we played a fast-paced category card game called Anomia, and in the next I summarized an article while we played.

In truth, the only homework I consistently did was listen daily to a meditation app created by the Center for Healthy Minds, at UW–Madison, which was founded by the psychologist Richard Davidson, known for his in-depth studies on the neurological effects of meditation. In our sessions, James and I talked a lot about metacognition, the act of recognizing one’s own thought processes rather than getting caught up in the spin cycle of them—decentering in psychological terms; mindfulness in Buddhism.

“I’m less interested in whether you can solve a logic puzzle than how you approach solving it,” he told me, in not allowing anxiety to become the obstacle. James is the calmest person I’ve ever met who wasn’t a Tibetan monk, and I told him so.

One day, I ran into Caleb in the hallway, and we greeted each other animatedly, per usual. I always get a little giddy when I see him. “You know I teach your tumor?” he said.

“You do?” I found myself strangely flattered. Jen once told me that he operated on seven-to-ten people a week. He’s in his mid-fifties. That is thousands of brains.

“Yes,” he smiled. “You know the movie Crocodile Dundee?”

“Sort of. From a million years ago.”

“There’s a scene where he and a woman are mugged by a guy with a switchblade. He laughs and says, ‘That’s not a knife,’ and pulls out a giant one and says, ‘That’s a knife’”

At home, I watched the charmingly retrograde scene on YouTube and admired Dundee’s bemused chuckle. His Bowie knife is huge.

I really wanted to hear Caleb teach my Bowie knife, but he demurred. A few months later, I went in for a yearly checkup with him after an MRI. All great, no need to come back for two years, he said. After we caught up on kids and life, I asked, “Why do you teach my tumor exactly?” He slid a plastic model of a brain across his desk and showed me that where the tumor had crossed over the midline it also crossed a major blood supply called the superior sagittal sinus. I knew about this but had forgotten. At the time, another surgeon suggested I have second surgery before the brain surgery, one that would run a stent from groin to head to embolize the blood flow, with a five percent chance of aneurysm on the operating table. When Caleb said no to the second surgery, that he was confident he could cauterize along the way if necessary, I put my brain in his hands. All these details, I had put into deep storage.

So, here we were, just chatting, and without his saying I could have bled to death, I knew I could have bled to death.

Sometimes now, walking down a sidewalk past a riot of blooming flowers or descending subway steps on a rainy night, out of nowhere, the macho Aussie’s words will pop up: “That’s not a knife. That’s a knife.”

Daphne is the author of the novel In the Land of No Right Angles and numerous essays, articles, and short stories. Her work has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, Vogue, McSweeney’s, Open City, and The London Review of Books, among other places. She’s been awarded fellowships by the New York Times Foundation, the Lannan Foundation, and the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and worked as an assistant editor at The New Yorker. Currently, she teaches creative writing at Pratt and is completing her second novel.

Brain, post surgery