Specimens

Marguerite Bunce

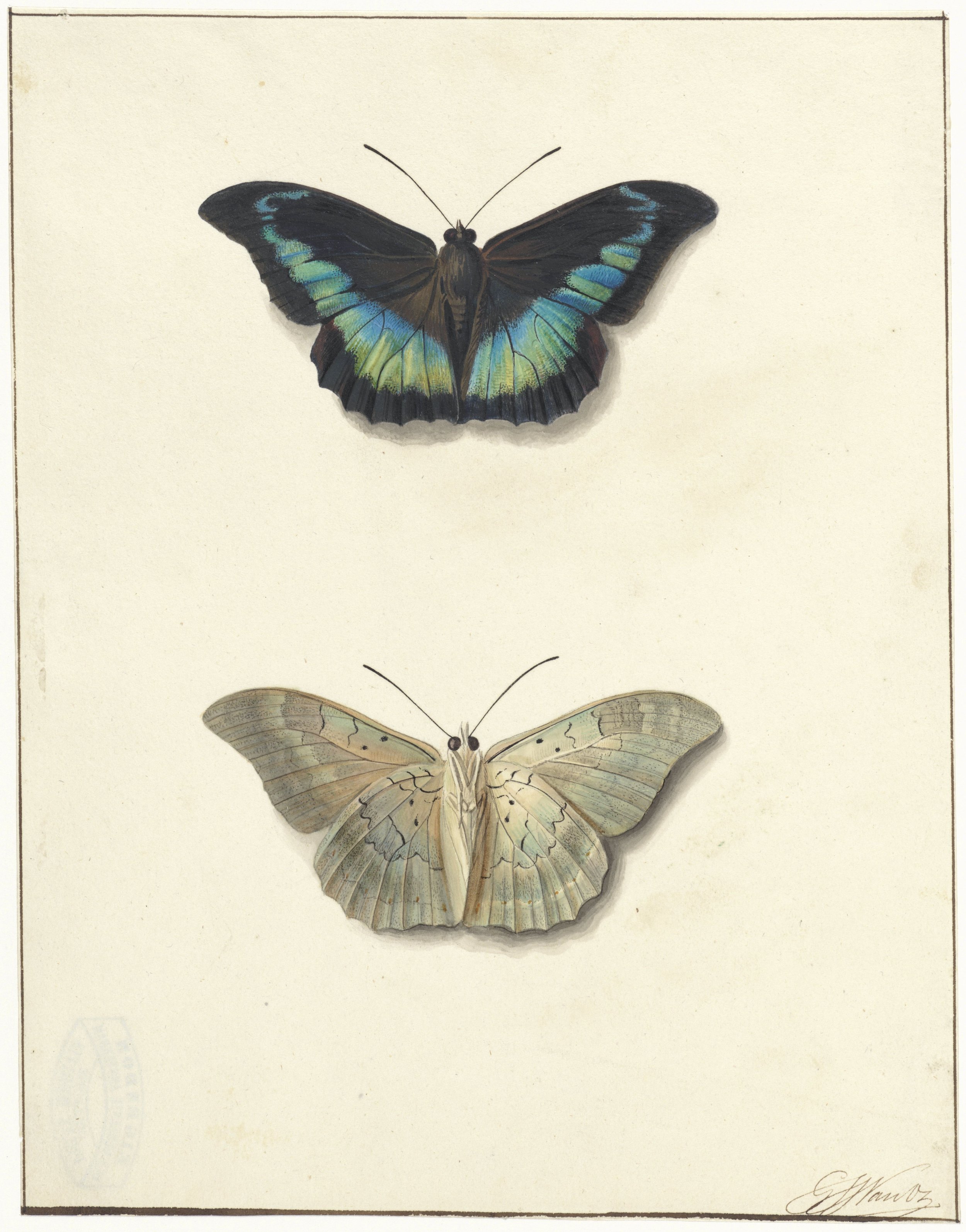

Image courtesy Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Word Count 817

I started collecting insect eggs around the same time I began catching butterflies. You only caught butterflies in order to kill them. That required a killing jar. My net was an old racket with netting from my old blue fairy costume. The killing jar was made by cutting a slit in the metal lid and inserting a strip of material. The local Pharmacy sold me small bottles of chloroform, which I dripped onto the material, killing the trapped butterfly. You had to pin the butterflies quickly after their death, because they'd stiffen up. The pinning board was foam, with a groove for the body. When the butterflies died, they folded their wings so they covered their thorax. In stretching the wings back so they were flat, you had to be careful not to lose too many of their glorious scales in the process. I didn't actually kill very many, and none of my specimens were in any way perfect. What I really wanted was to hatch my own butterflies.

To that end I found caterpillars. The biggest were the Orchard Swallowtail, which lived on citrus leaves disguised as bird droppings. They were quite disgusting with their red osmeterium, which flared out when you touched them. These glistening fleshy antennae also exuded a nasty smell. The caterpillars got bigger and bigger, and became bull like beasts. An element of horror crept into my game of keeping things alive to see what would happen.

Some time before, I'd found a grid of small green eggs. The underside of a leaf beaded with a colour matching crust of potential. I put it in one of my many jars and waited.

Television was in its late infancy too. And like many kids, I watched a lot of it. When the cybermen appeared on Dr Who, with their uniformity, their wrinkling silver skin, and their unblinking eyes, my horror marched in time. But it was the episode where we saw the cybermen hatching which plumbed my depths. In a white lab-like room a wall was filled with pearly globes of translucent leather. While I watched, each cell was burst open by a fully formed monster.

My jars were sources of guilt. I'd found skink eggs and put them in soil and only by luck rescued the hatched lizards from who knew how many hours of frantic circling.

Later in life I'd turn once again to hatching silk worm eggs. For some reason, I often felt depressed, and this time I'd been pointed towards a group which talked about their stuff. When it was my turn, I offered something up which everyone there would understand as a good reason to be upset, but which wasn't. My recent abortion had been a wonderful experience, whereas the pregnancy was nightmarish. So I told the group I'd had an abortion and pulled a sad face. It was uni, and one of the boys was in a lab and mentioned that they had silk worm eggs. I jumped at the possibility. All I had to do was find enough mulberry leaves in the inner city. Mulberries are understandably unpopular trees in tight packed urban environments, particularly in cities filled with fruit bats and fruit eating birds. I'd had a good source of leaves but now all the young leaves were gone, with only leathery ones left at the end of summer. Further searching had resulted in a perfect tree, not too far away. I put the leaves in the box and left the now nearly mature grubs to feed for the night. When the lid came off in the morning I was faced with unimaginable disaster. All the caterpillars were writhing and their innards were bursting through their skins. I took the box into the backyard and trod on all of them.

My childhood had hit a hitch at around ten years old. I couldn't understand why I felt so sad all the time. Afternoons were the worst, as the light fell. At night I couldn't sleep. I listened to the television, hearing the theme music, then the conversations. I finally told my mother and I was taken to a special doctor. He asked me if I had my period. Not yet. Then he gave me tablets to take day and night. My mother told me the reason for my sadness. It was because I'd changed schools and was now expected to work. My teacher told my mother later, that she should have been informed that I was taking downers.

Of course, I'd forgotten about the green eggs. Before I opened the jar, I could see them. Glassy green aliens marched across their cracked eggs like miniature cybermen. I knew what they were. They were stink bugs. But knowing didn't help. I was playing midwife to an invasion force. And I didn't tell my mother. She already knew too much.

Marguerite grew up in Sydney, Australia, where she published poetry in some anthologies and won a couple of prizes. When her poems became too long for traditional publication, she wrote a libretto for an opera based on a Bocaccio story from the Decameron. “The Remedy” was performed by the Sydney Metropolitan Opera company. Short films she wrote were shown at the National Film Institute in London and elsewhere. She currently lives in the south of France where she is experimenting in new forms of writing, such as the essay published here.