Affairs In Order

Patty Dann

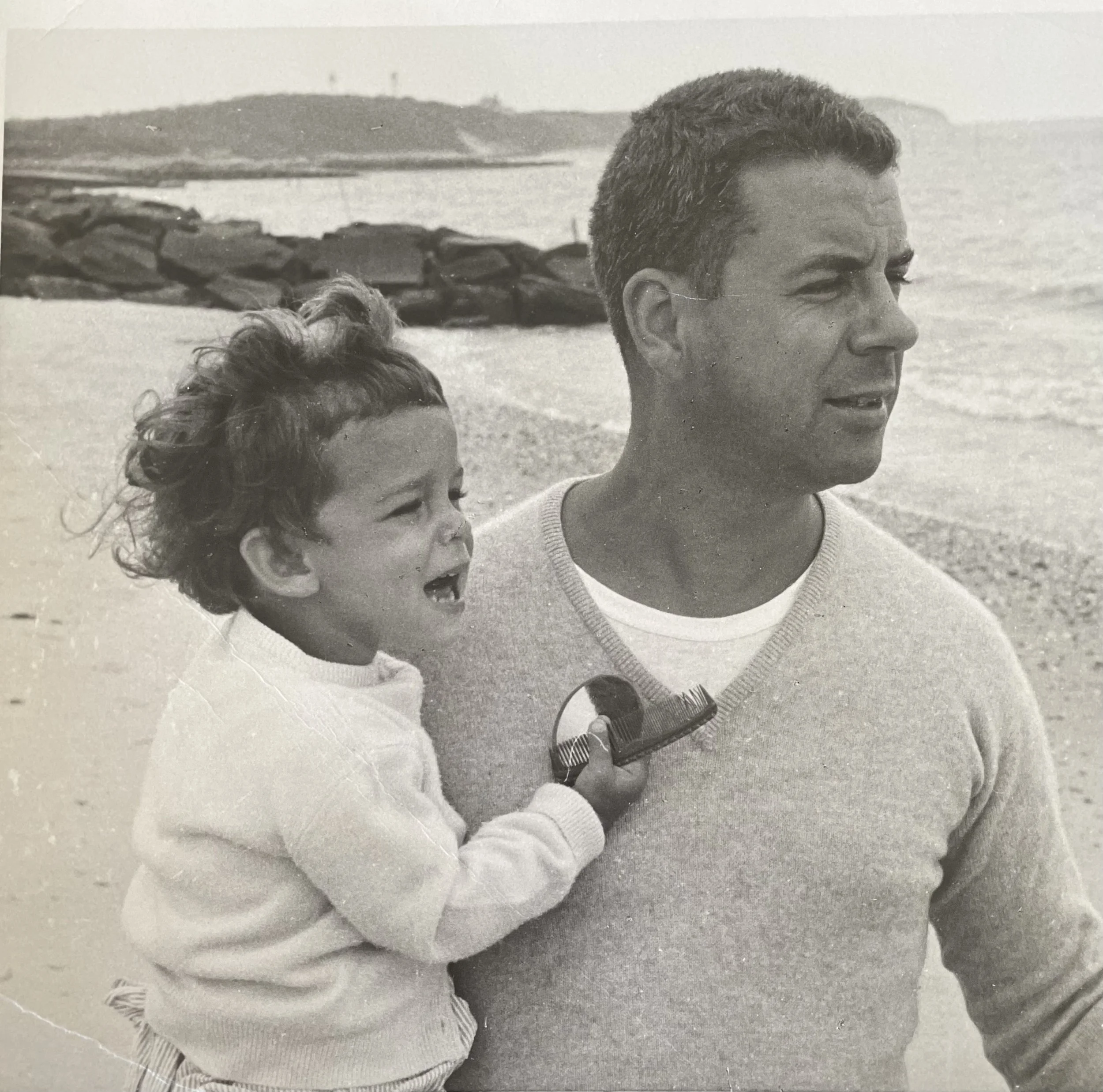

The author with her father

Word Count 758

I last saw my mother in Covid times, when I stood among pale blue hydrangea bushes and waved goodbye to her on the balcony of her Memory Care unit. Minutes later, I got a call from a lawyer saying one of my father’s lovers, Barbara, had died and named me as the Executor, which was news to me.

I was born with a caul inside the amniotic sac, in what is known as a veiled or mermaid birth. Legend says this should prevent me from drowning, but it did not prevent me from becoming unhinged at the task of getting my mother and Barbara’s “affairs in order.”

Sometimes, overwhelmed by the paperwork and emotions of thinking about my father’s passionate adventures while grieving for my mother, I would call my son across the country to hear his voice. We often lie to each other. He’d had to weather my own romances when, at age four, his father died. I would ask him how he was, and he’d say, “I’m living my life, Mom, I’m living my life.

Barbara was a TV director when no other women were. My father was a TV executive in NYC and often “on the coast,” as we called it, as if it were Shangri-La. My mother worked at the local suburban paper and took care of her three unruly kids. She had long-time sweethearts after my parents split up, but her only marriage was to my father, while my father married two more times. Once divorced, my mother would put on polka-dot dresses, a heavy mist of Chanel No. 5 and pinch her cheeks before she went out on the town.

Both my parents died on May 27th, although four years and a thousand miles apart. By then, they had been divorced for 50 years.

Barbara was not a stranger to me, but when we were introduced, I did not know her connection to my father. I had met her at a summer writers’ conference in the mountains, where she taught a class on screenwriting. She, like my mother, was a petite woman, smart as a whip with anguished and alluring eyes. Barbara gave us the assignment to write about our fathers’ childhoods. A small group of us sat at a picnic table and wrote by hand in our notebooks.

I wrote about my father, who grew up in an Orthodox Jewish home in Detroit, had polio, and used to limp to watch other kids play sandlot baseball games, his leg bloody from his iron brace. After I read my piece out loud, and the other students gave their comments, it was Barbara’s turn to critique my work.

“I know,” murmured Barbara, as she looked across the table from me in the mountain air, and in that moment when she said, “I know,” I knew what she meant. I understood with clarity, like swimming in a lake when it goes from warm to cool, and you know the temperature will again change if you swim a little further. Barbara had seen my father’s bad leg and every other part of him as well.

It remains a mystery as to why Barbara chose me to be her executor, whether I was an imagined daughter she never had, or simply because other people on her list had died. Whatever the reason, on the morning of Memorial Day, two years after my mother’s death, I finally finished all the paperwork for her and for Barbara, all the signing, notarizing, scanning, and copying.

I walked triumphantly to a bench I’d adopted a year before to honor my parents near the Soldiers & Sailors Monument above the Hudson River. Military men and women were setting up wreaths in preparation for the day’s celebrations.

I sensed the Hudson River was there, as I sat on the bench, but I could not see the water clearly, because of all the trees. What I mostly saw was an eruption of spring colors, the lime and moss hues of maple and oak leaves, and the deep lush darkness of the pines, while Canada geese, red-tailed hawks, Kestrels, falcons, and songbirds swooped overhead.

On the bench was the inscription I’d come up with in a weepy moment-- “I am with you in all seasons,” a phrase that somehow made me sit on that bench practically every day for a year after my mother’s death.

Before my mother had married my father, she insisted that he increase his vocabulary. One word she taught him before they wed was verdant. “He should know other ways to say green,” she explained, as if that were obvious, as we stood at the sink in my childhood kitchen, looking out at the deer in the snow.

I sat quietly on the bench, breathing in the honeysuckle air. The American flag was waving at half-mast because of recent mass shootings. The Black Lives Matter flag waved too. A Marine band was warming up. A bugler practiced the opening notes of The Star-Spangled Banner.

A man in a blue wool Civil War Union uniform approached me at the bench. I stood and greeted him in a kind of curtsy, because it seemed the right thing to do. He saluted and told me his great-great-great grandfather had fought at the Battle of Antietam and was wounded in the arm but survived. And then, as the Marine Band began to play America The Beautiful, I burst into tears, because my parents were dead, and the world was coming back to life, and the world was falling apart. The Marine band blared their horns as fighter jets flew overhead. It was time for me to live my life, as my son would say. It was time for me to re-enter the verdant and crazy world.

Patty has written seven books, both fiction and non-fiction. Her novel, Mermaids, was made into a movie starring Cher, Winona Ryder, and Christina Ricci. The Butterfly Hours was chosen as One of the Best Books for Writers by Poets & Writers. She has written three Modern Love columns for The New York Times.