The Long Marriage

Kate Stone Lombardi

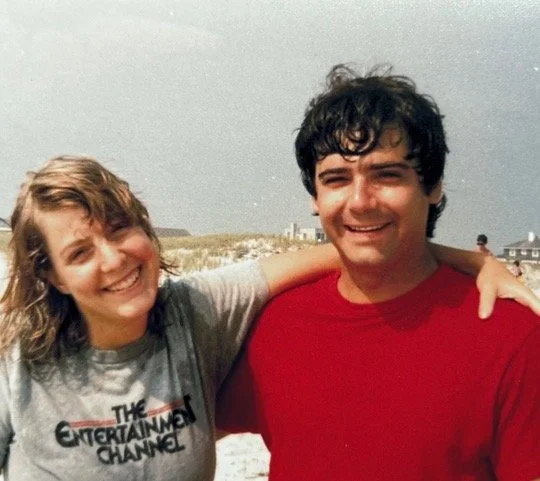

The author, with her husband, in 1982

Word Count 2202

A few years ago, I began noticing brown age spots spreading across the back of my husband’s hands. His father had these same spots in the same place.

“We’ve been hanging out together a long time,” I say to Michael, as we scroll through our respective devices on our faded green corduroy couch. “I can’t believe it’s been 42 years.”

“Forty-three,” he replies, matter of fact.

Michael knows my math skills are abominable. Early in our relationship, he thought I was faking it – trying to be funny. But honest to God, sometimes I cannot remember how old I am, let alone how old our marriage is.

I was 24 when I met Michael, 25 when we got engaged, 26 when we got married, 27 when I got pregnant with our first child. We barely knew each other when we said our vows, though of course we thought we knew everything.

But how could we? We didn’t even know ourselves.

Those early years are a blur, but I do have illustrations. Our bookshelves are filled with dozens of photo albums chronicling the first few decades of our marriage.

There we are on our tropical honeymoon - playful, sensual, and impossibly young. I was so pretty! I’m starry-eyed looking at my brand-new husband. Michael was so handsome and full of kinetic energy. Next come photos showing me swollen, pregnant and proud, looking at the soon-to-be occupied crib. (That crib had bumpers in bright primary colors, pillows, blankets, stuffed animals and a mobile of little stars; all items that my daughter would later eschew for her own child, as they are now considered a smothering risk. Well, except the mobile. That’s a strangling risk.)

During the years the kids were growing up there are few pictures of just Michael and me. Mostly it’s photos of the kids - as babies, toddlers, in school photos, as sulky teenagers, half turned away from the camera. By the time we got to college graduations, weddings and the first grandchild, photos had gone digital, and those memories are stored on computers or in the cloud, not in faux leather-bound books.

How can photos possibly illustrate the reality of a long marriage anyway? The tears and the anger don’t make for good pictures. The moments of grace can’t be captured either.

Even the bumpy day-in-day-out ride that ultimately forms the bones of the marriage is elusive to portray. The family grows. Miscarriages. A child in the emergency room. Sleepovers. Birthday parties. A wild teenager. A near-fateful car crash with said child. A triumphant soccer goal after a lousy season. Michael toting our brand new, ridiculously heavy video camera on a family trip to Glacier National Park. Me angry because most of the footage ends up being of scenery and not the kids. Fussing over what pizza toppings we should choose. Just once can we have broccoli and not mushrooms?

I can remember staring out a restaurant window – it was one of those places that had a built-in play area for the children – looking at the horizon, the sun setting over suburban sprawl, and wondering how I got to this life. And if there was a way out. I’m sure Michael had similar fantasies.

The author and husband, 2024

Marriage does not have a clear narrative arc.

More time goes by. We’re in our 40s, 50s, 60s. Our grandparents die, and then parents. We have conversations about whether we want to be buried or cremated, and whether we believe in God. In the pictures, Michael’s hair gradually turns from black to flecked with grey, to a beautiful silver in those images. It’s still a thick mane. Mine appears in different shades of blonde, depending on my hairdresser at the time, until finally, I give up, and the fading blonde mixes with silver.

Another phrase we say often is, “It’s a good thing you’re cute,” usually when we’re driving each other crazy. From the day Michael and I met, we couldn’t keep our hands off on another. The fact is, we’ve always been wildly attracted to each other. Sometimes, I look over at him, and he’s still that hot guy I dated.

When we married, I believed we were already adults. After all, we both held responsible jobs working for a public television station. Michael had an MBA and I would go on to get my Master’s degree. We could afford our rent and even put aside money toward savings.

It was early 1980s Manhattan, and on weekends, we partied with a wild pack of college friends.

On Sunday afternoons we canoodled on a picnic blanket in Riverside Park, passing sections of the New York Times back and forth. It was a mighty paper package then, full of advertisements. I was going to say, “thick as a telephone book,” but that, too, is an anachronism.

I have a sharp memory of meeting the man who would become my father-in-law. He was far younger than I am now. His hair was thick, wavy, and black. He was short and rotund with a thick Southern accent. When he answered the door of Michael’s childhood home, I was surprised not only by his shape (Michael was slim) but also by his father’s dog, leaping up next to him.

The dog looked like a hairy rat, yipped incessantly, and bounced like a superball – all the way up to my father-in-law’s shoulders. An unfortunate mix between a miniature poodle and a chihuahua, the dog was also the runt of the litter. My father-in-law adored this high-strung creature and named him “Sonny” after Sonny Jurgensen, a famous NFL quarterback.

Back then, Michael didn’t talk about his childhood. When I asked him about specifics, he always said he “couldn’t remember.” Decades later, he would reveal that his father had been a bully who had fits of rage. Once, when we were house shopping in the late 1980s, Michael nixed a property because of a tree in the backyard. There’d been a weeping willow tree at his childhood home - one from which his father took the switch he used to hit the kids.

I never saw this side of my father-in-law. He was kind to me. He’d mellowed by the time I met him, and besides, I wasn’t his kid. And I couldn’t reconcile this man who tormented his boys with his soft spot for this pathetic dog.

Now, when I look at my husband, I wonder what of his father, besides those age spots, resides in him. He’s been a kind and tender father and is a besotted grandfather. It has taken decades for me to understand the forces that shaped him. And I think the same holds for how he’s learned over time to understand me.

As a variation on, “We’ve been hanging out together a long time,” sometimes I say to Michael, “We’ve been through a whole heap together.” I now understand why the wedding vows hit the highlights they do. “For better and for worse.” Certainly, we dished out plenty of “worse” to each other, and there were times when I really didn’t think our marriage would make it.

“For richer and for poorer.” Michael went through dramatic highs and lows during his career, and after 30 years, he walked away from his lucrative corporate finance job to pursue his lifelong dream of attending Meteorology school. (Cue the “poorer.” We had one kid in college and another in high school at the time.) My career has been steady but freelance, and not particularly well-paid.

Let’s not forget “in sickness and in health.” Sickness comes in many forms. Michael suffered depression and I have a full-blown anxiety disorder. Early in our marriage, neither had any understanding of our own issues, let alone each other’s. Why couldn’t Michael just pull himself together and buck up when he felt down, I wondered? He, in turn, couldn’t fathom why I was unable to “just relax.’’ We both had so much to learn.

Then there were the medical emergencies. Mike feeling “off” and ending up in a hospital cardiac unit with a life-threatening blockage in his artery. The young cardiologist who thoughtlessly told me, “Yeah, your husband has what we call “a widow maker.” The panic in my own chest upon hearing this.

My Dad’s long descent into dementia, and his eventual death, and my own psychological and physical spiral during that time. Michael would drive, cook, hold and soothe me. “Tell me what I can do today to be helpful,” he said, when I’d come home devastated from another heartbreaking day.

There was 9/11, when my husband was on 9:00 am American Airline flight #1 from JFK to LA, and the time that passed before we knew if his plane was one of those hijacked. Our kids calling from their respective middle and high schools, choking, “Is it Daddy?” through tears. And then Michael, using one of those old phones attached to the airline seat in front of you, finally calling and sounding cranky: “I don’t know what’s going on. My cell isn’t working. Our flight is delayed. We’re still on the ground and I’m going to miss my meeting. Hold on. The captain is making an announcement.” He paused and when he spoke again, it was with a changed tone, “that’s weird. The captain just asked us to pray.”

I was watching the first tower fall on TV as we spoke. All I could think to say is, “Get out of the plane. Get out of the plane.”

Now that we’re getting older – I’m 67 and he’s 72 – even routine medical procedures worry me. Last week, Michael was getting a cataract removed. What should have been routine was slightly complicated – the cataract was beginning to flake off into the eye, and a retinal surgeon was on call.

Before he drove to the hospital that morning, he brought me a cup of coffee in bed. He made it for me even though he was not allowed to have anything to eat or drink for 12 hours before the procedure.

Michael looked exhausted when he left, and I had a nagging worry that something would go wrong. He wore a blue and green flannel shirt he could unbutton, so he didn’t have to pull anything over his head after the surgery.

A few hours later, I took the train to the city hospital, so I could join him in the recovery room and drive us home. My driving makes Michael nervous, but we figured he’d still be sufficiently drugged not to freak out.

Walking into the small area cordoned off by blue curtains, I find my husband lying on a gurney, wearing a hospital gown, socks and what looks like a blue shower cap. An IV is in the crook of his arm and he’s drowsy.

“There you are!” he says, smiling. “Come over here.”

I walk over and give him a gentle hug.

“You’re so beautiful!” he says. “I forgot how beautiful you are. Turn around. Wow!”

I joke to the attending nurse that I’d like an extra vial of whatever drug he is on “to go.” But the truth is, Michael often tells me how pretty I am. Still, he’s pretty looped.

“Have you ever really studied the lyrics of “Leader of the Pack?” he asks, referring to the old 1960s song.

“Hold on, honey. I’m just texting the kids that your procedure went fine.”

“Ok.” Then five seconds later, he asks, “Have you ever really studied the lyrics of ‘Leader of the Pack?’”

I get him home and Michael changes into his pajamas. I make dinner, remind him to take his eye drops and we crawl into bed early. I feel the familiar weight of him when he gets in – the initial dip in the mattress and then the settling in. Periodically through the night, I will reach over a hand or foot to make sure he’s still there. If he’s too quiet, I lean over to make sure he’s breathing.

If he awakens during one of these “live checks,” I lay perfectly still. I don’t want to get bagged.

Our society talks a lot about the individual aging process. But “the aging marriage” is so much more than the sum of its parts. Yes, Michael and I drive each other nuts with how often we repeat the same story, how messy I am, how rigid he can be. Of course, we both have character flaws and annoying habits. And when we’re being mean, we have our go-to verbal shots of “That’s just like your father!” or “You sound just like your mother!”

But long-term marriage is mastering the art of understanding what is simply not going to change and then letting it go. It’s kindness. It’s knowing every mole and individual quirk of your beloved’s body. It’s thousands of shared memories, with an accompanying shared playlist of your life together.

It’s tenderness.

You grow up with your siblings, but for a relatively short time. You reach true adulthood with your husband or partner. I remember when I used to see elderly couples holding hands on the street and think, “Oh that’s so adorable.”

Yeah, it’s sweet. But it’s also deep. Formidable. And incredibly lucky.

Kate is a journalist, author and essayist. For 20 years, she was a regular contributor to The New York Times. Kate’s work has also appeared in the Wall Street Journal, Time.com, Good Housekeeping, Readers Digest, AARP’s “The Ethel” and other national publications. She is the author of “THE MAMA’S BOY MYTH” (Avery/Penguin, 2012), a nonfiction book on raising boys.