Samos, Samos

Bex O’Brian

Word Count 1271

On a hot, dusty Sunday, my mother, little sister Sophie, and I are on a bus heading to the far side of the Greek Island, Samos. An island that, at this moment in time, is struggling with the horror of drowned migrants fleeing drought, war, and famine washing up on its shores.

But in 1977, we were just trying to get to the other side, and all we knew of trouble was the Greeks and the Turks hated each other, and should war break out, Samos, the island closest to Turkey, would be ground zero. Being seventeen, I didn’t care. I was just happy that the place was full of soldiers who took me out on dates and allowed me time away from my mother, who had chosen that trip to start going through menopause, yet another natural occurrence in her body that she was completely ill-prepared for. Pregnancy and digestion are two others that immediately spring to mind.

I don’t know why we needed to get to the other side of the Island, there were no ruins or secret beaches. Certainly no great restaurant. This was before the EU, so fruits and vegetables weren’t winging across borders. There was plenty of fish, but I’m allergic to seafood, so for the last three weeks, all I had eaten was pork chops. I could have had a tomato salad, but I hate tomatoes.

At the beginning of the ride, we were the only passengers. It wasn’t a school bus, a tour bus, or a city bus. It was shorter than all those, with hardback seats. The driver seemed to be having trouble with the gears. We ground and lurched along through the barren, windswept landscape. I was relieved when we picked up a few more passengers and decided to eat the orange I had brought.

It was the most delicious orange I have ever eaten.

Then I had sticky hands and nothing to clean them with.

Mother and Sophie sat in front of me. I could see Mother surreptitiously check her pulse. She lifted her hair repeatedly off her neck. Once, she stood up, only to be thrown back down onto her seat.

We were on this trip because a gay friend of my mother’s said Samos was the undiscovered island and the best. She was probably drunk when she booked the tickets. That’s how things got done in our family.

We started in Athens, and even though we hadn’t travelled much, knew right away The Plaka was a tourist trap and steered clear. I might have gotten a decent meal if we hadn’t, but at least we felt good about ourselves eating at dives. It was the rare moment we all felt good at the same time. A current of anxiety ran back and forth between my mother and me. She could only afford this trip if she didn’t miss writing her weekly column. Our trip was the subject, it was supposed to be funny. Nothing we were doing was remotely amusing. She was scared, panicked, and fighting her body which was acting up. Hot/Cold. Racing thoughts/undying dullness. Mother looked to me to ease these sensations, but her panic was unspooling me. I could barely look at her, so great was my fear that all reality might slip clean away and I’d be lost. Mother sensed something was up, which made her more clingy. Long divorced from my father, it had been my role to be her rock, her reader, her confidant. And now she needed me to know directions, not let cab drivers rip us off, and figure out currency exchange. But I kept failing, fumbling, losing the thread.

My sticky fingers were really bugging me and I was looking around for anything damp when the bus, entering the town we had gone across the island to see, crashed. Not so much crashed but got itself wedged in the narrow street. It made no sense. Assuming this was the bus’s regular route. The other passengers started talking wildly and yelling at the driver. I looked out the window right into the house we had ground up against. There were a couple of kids, about the same age as Sophie, falling about laughing, This was big news.

Finally, one of the screaming passengers stormed to the back of the bus and kicked open the emergency door, which infuriated the driver. But it only took a moment for the rest of us to realise that we were better off than on, and our exodus cut him off before he could keep us corralled.

Mother and I helped an old woman down, who shrugged, “This is not a scheduled stop.”

This side of the island seemed to have no air, no wind, no shadow, no trees.

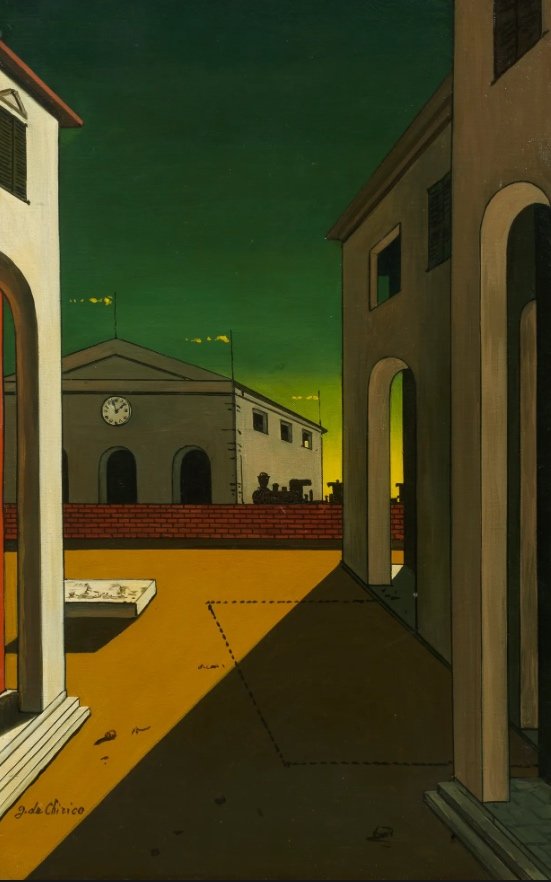

We found ourselves in the town square. Nothing moved. Nothing was open.

I thought at least I could go down to the small beach by the seafront and wash my hands. There was a hum as I approached, enough so that I felt it in my chest. Mother and Sophie, shading their eyes, watched me silently. On the first ancient stone step leading down to the beach, I saw the fish, thousands upon thousands of small dead fish washed up on the shore. The hum was the flies which rose and fell like a thick black blanket.

Mother, still shading her eyes, turned as if she knew what I was looking at and that somehow I was at fault.

I backed up the step. The sea beyond was slate, didn’t reflect the sun, and was bizarrely motionless. No wonder those fish had died.

What had happened to the old woman we had helped off the bus? And the ringleader who had kicked open the door? Even the kids laughing? In all the silence, they now seemed impossible. We were completely alone.

None of us spoke. Sophie pointed to a cafe at the far end of the square. It was closed, but the awning was up and offered some hope of shade.

Walking, bent by the sun, Sophie said she needed to pee. Mother looked around. Sophie had been peeing all over the island behind cafes, cars, and beach umbrellas. Another year or two and she would have been too old, she would have been like Mother and I, stepping into dark corners of dark cafes and peeing in bottomless pits. In the wide-open plaza, there seemed to be no place to go.

Mother took Sophie by the hand, “Hold it.”

We were so sun-battered by the time we reached the shuttered cafe that we sat in stunned silence. We might be the last people on earth.

The boy, when we noticed him, was sitting by the closed entrance in deep shadow, his chair leaning back against the wall. His feet don’t touch the ground. Sophie remembers his gun resting against the wall. I remember it on his lap. He didn’t look at us as he picked an insect, shaped like a praying Mantis, but much bigger, off his shoulder and placed it on his stomach, where it began yet another torturously slow crawl back up to his shoulder.

My mother, who had a terror of bugs, buried her face in her hands and moaned with fear.

That’s where memory ends. I’ve lost what came next. How did we get back to the other side of the island? What happened to the bus? Did we get anything to eat? All gone. Except for the terrible unease of that day and how none of us could offer any solace or reassurance. That has not been lost to me.

Bex lives mostly in France with her husband and their dog. She’s been scribbling around on various projects for the better part of thirty years and made very little money as a result. Thus conditioned, she is thrilled with the advent of Dorothy Parker’s Ashes. She is the author of the novels (Under Bex Brian) Promiscuous Unbound and Radius, also available here. At present, she’s working on a new novel entitled, The Last Lover.