These Boots Were Made for Walking

Laura Carraro

Word Count 1763

My mother and I walk up from Riverside Drive toward Broadway. It’s her eightieth birthday, and I’m taking her to lunch at a nice café where, rumor has it, Jennifer Garner once worked as a hostess. She won’t be impressed.

After lunch, my plan is to buy her a special present. No paperback this year, or heart-shaped trinket for her collection. No orchid or CD. It’s mid-September. The sun is shining as we walk up the gentle slope that is beginning to feel like a hill. The air is warm, but a breeze reminds us to relish this day more than one in June because the cold season is just ahead.

The soles of her ladylike Mary Janes clack clack clack on the sidewalk. She has always been a fast walker, and her age hasn’t slowed her down. I am quieter than her in my rubber-soled shoes. I would not be described as a masculine woman, but I always feel that way around my mother. “Are you sure you can walk in those things?” I ask her. My mother took a fall on 125th Street recently, having tangled her foot in a discarded plastic bag.

There had been a fire truck parked near where she fell. When I saw her later that day with a swollen lump on her forehead, she chattered excitedly about how the firemen had taken care of her. She has always had a weakness for firemen. “First I fell on my knees,” she told me. “But I didn’t run my pantyhose.” I call my mother a girly-girl because she wears pantyhose and a skirt when she goes out, showing off her toned calves.

We hop on the 104 bus towards 78th Street. People offer her a seat, but she declines. It was hard enough convincing her that we shouldn’t walk the twenty blocks to the restaurant. She is the quintessential New Yorker. She walks constantly, and, though she has recently given up jaywalking, she doesn’t stop at curbs when the crosswalk lights are red, but pivots to wherever the light is green, traversing the city in a Pac Man pattern of right angles. I have become softened by years of suburban living, and often want to ask her, what’s the rush?

While we eat eggs benedict and sip on crisp, cold pinot grigio, I gaze out the window, across Columbus Avenue, to the blacktop yard of the middle school I attended as a preteen. I am reminded of the flat thud of poorly inflated pinkish red playground balls, and the whistles of the monitors who were mainly there to break up fights.

We were poor kids, but amongst us there were different kinds of poor. My mother, a divorced and unsupported secretary, put food on the table. We had electricity and a warm home. Sometimes the phone was shut off but never for longer than the next paycheck. I always had a coat in winter. I was hard on my shoes, though, and they didn’t always last for as long as my mother would have liked.

My mother has a glittery silver bow in her hair. She has worn a small bow for as far back as I can remember, clipping her long bangs back to one side. When I was a little girl, she used to put a grosgrain ribbon in my hair every morning, tying it up in a bow on the top of my head. Sometimes, when she hadn’t had a chance to do the ironing, she’d pull the shade off the lamp in the living room and flatten my ribbon from the heat of the bulb, pulling it back and forth the way a shoe shiner works a rag. As soon as she dropped me at school, I’d pull the ribbon off and put it in a pocket.

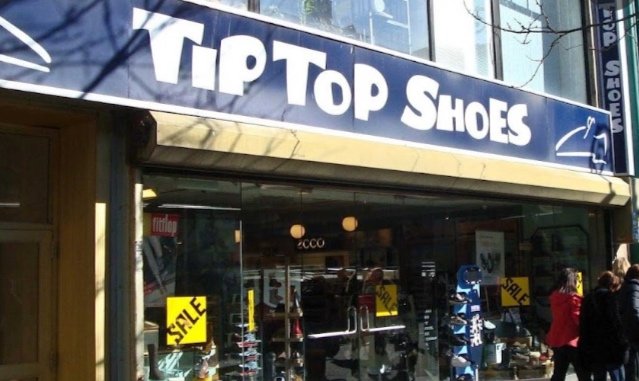

“I have a surprise for you,” I tell my mother over the din in the restaurant. “I’m going to take you to Tip Top to pick out a new pair of boots.” “I have boots,” she answers. She swirls a soggy piece of English muffin in egg yolk and doesn’t look up.

“Yeah, but I want to buy you quality boots. Something sensible.”

“I am sensible,'' she says. “I like the boots I have.”

“Those cowboy boots?” I am ashamed, as I say it, that I have not yet outgrown the teenage tendency to critique my mother’s attire.

“Stop picking on me,” she says beneath her breath.

Last week she tried on a pair of blue lace-up ankle boots at Urban Outfitters and was frustrated that they weren’t a good fit. I tried to explain to her that they were designed for twenty-year-old women. I asked her what she would have worn them with, and she said, without hesitation, that they’d go well with a short skirt and tights. My mother once taught me that if you’ve got them, flaunt them and she does not miss an opportunity to show off her legs that still have muscular definition all the way up her thighs. I, on the other hand, dress to disappear.

Once, when my mother was in a support group for divorcees, heartbroken and struggling to survive, a man turned to her and said, “Look at you. You’re so plain. You don’t even wear jewelry.” She still remembers the sting, and how she vowed then and there not to be plain anymore. She started buying jewelry and scarves, berets in pastel colors, and pocketbooks in every style. Like many New Yorkers, she purchased them from the street vendors who ply their wares on Broadway. To this day her bedroom is a medley of colorful scarves, beaded necklaces, belts, and sashes. They are draped, like art, from hooks and dowels. She doesn’t leave her apartment without earrings, necklaces, a scarf, and an assortment of her many rings. If she had a signature sound it would be jingle jangle.

My mother married when she was twenty-one and graduated college with a pregnant belly under her cap and gown, a valedictorian with morning sickness. She was washing cloth diapers and boiling baby bottles by the time she was twenty-two. It was as though her four children just happened to her. And I guess that is what it was like in the nineteen fifties when birth control was all made from breakable rubber. One day she was a smart girl who refused to major in Home Economics, and the next day she was a twenty-two-year-old married woman with a baby.

When I was twenty-two a generation of women had burned their bras. She has worked more hours than I have, held a family’s finances together for more years than I can match. She got on the subway every morning and worked jobs she hated. She worked with shingles, worked with the flu, and dragged herself to her job during snowstorms. Her life has been harder than mine. She taught me to work hard, but there is no question that I have also had good luck.

I want –no, I need-- to buy her a pair of boots she would never spend the money on. I want to buy her safety and comfort, but I think I also want to pull her up with me into the economic comfort I have acquired. We are people now, I mean to say to her, who can buy expensive shoes.

When we get to Tip Top, somewhere I would have loved to shop for shoes as a kid, my mother is resistant. We gaze at the shoes in the window before we enter, and she says she doesn’t think she’ll find anything she likes in there. I want them all. Shoes, more than any other item, are indicators to me that I have money now. I’m not that poor girl. My mother is not that poor girl’s mother. The air, when we enter, smells like suede. The mother of an acquaintance is sitting in a chair waiting for a salesman to bring her selections. Her feet, with peds stretched on them, are swollen. She has already tried on several shoes, which are scattered by her feet. As I chat with her, my mother beelines for the display shelves.

“This place is expensive,” she whispers to me when I join her. She’s holding a short slip-on boot with studs. I reach up and grab another boot, a clunky rubber-soled duck boot just perfect for the slush of the New York winter heading our way. “I don’t need those,” she says. I look over to my acquaintance’s mother. A salesman is perched in front of her and is slipping a sneaker onto her foot. My mother pulls out another boot, looks at the price on the sole and puts it back. “It’s your birthday, Mom. Don’t worry about the price. I want you to get what you want.”

But do I? The next boot she picks up is snakeskin. I look down at my own shoes. I’m so proud of their arch support, the roomy toe box, and the nonskid soles. If I had to, I could run in them. If my shoes were a car, they’d be a Volvo. My mother seems to want a Mustang convertible.

When the salesman takes the heel of her foot in his hands and slips a boot on her foot I am thrilled for my mother. It’s as though I have brought her for a special pedicure. What a luxury, to have your foot sized with a metal Brannock device and then have a shoe slipped onto your foot by a solicitous salesperson whose job is to ensure a good fit. I want to turn to the customers at Tip Top and make an announcement. Not everybody gets to do this! Most people buy their shoes from a rack. There is no one there to squeeze their toes. We settle, after much debate, on knee-high boots for bad weather. They’re not as ornamental as she would have liked, and I’m not so sure about ankle support, but we have managed, at least, to make a selection.

We walk all the way home from 72nd Street to 98th, stopping occasionally to look at shiny things in store windows. By the time we get back to Riverside Drive my feet hurt but hers don’t. We hug goodbye. She tells me she’s had a wonderful day. I wish her a happy birthday one more time. “Are you sure you like them?” I ask, gesturing toward the Tip Top bag in her hand. She says yes but I’m pretty sure she's lying.

Laura is a writer who lives in New York with her husband and their rambunctious terrier. When not writing, she’s in her studio making art or working with high school students as a writing tutor. She earned an MFA in Creative Nonfiction from Sarah Lawrence College. Her work can be found in Motherwell and in upcoming editions of Sonora Review and Hippocampus Magazine. Her memoir, PROOF OF LOVE, is out in the world seeking representation.