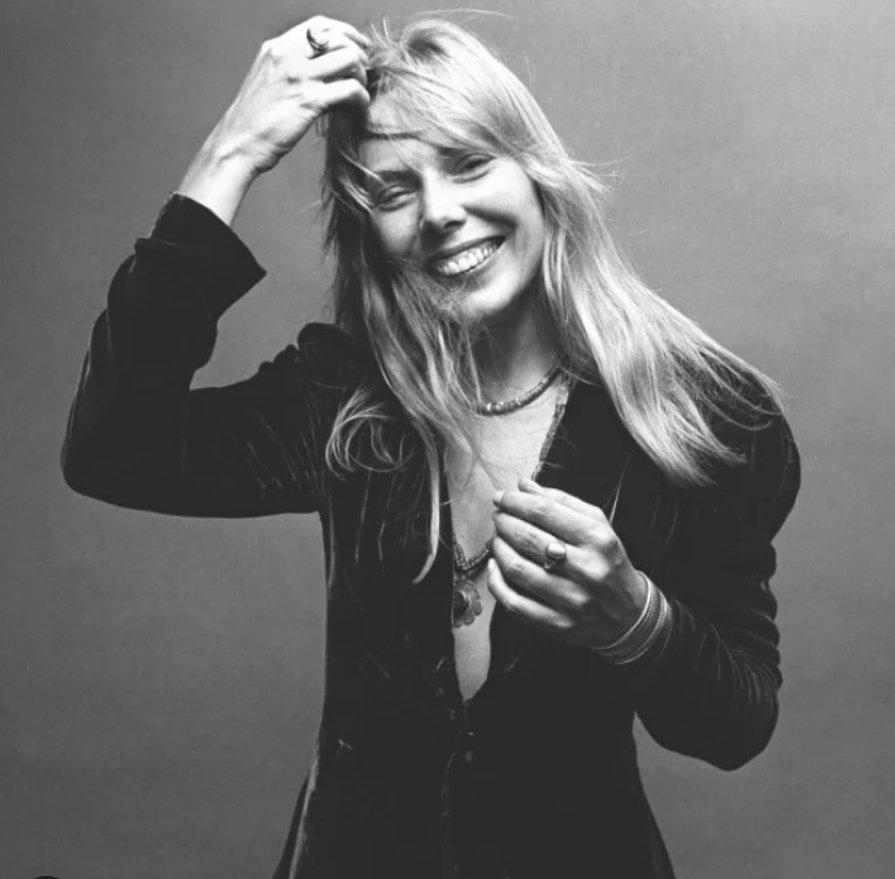

Joni

Sheila Weller

Word Count 12547

The following is an excerpt from Sheila Weller’s seminal book, “Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon and the Journey of a Generation.”

The word-of-mouth that Joni Anderson Mitchell had earned for herself in New York accompanied her to Los Angeles. She arrived around Christmastime with her new, devoted manager Elliot Roberts and her boyfriend and chief champion, David Crosby. Having as strong-minded and talented a woman as Joni for a girlfriend was new for David, who had dominated his previous girlfriend Christine Hinton (he'd broken up with Christine when he'd fallen in love with Joni, but they would later reunite). All he’d had to do was shout, "Christine! Joint!" and she was rolling and handing him a slender reefer. "Christine was always anxious, always ready to please," remembers Hinton’s then-close friend Salli Sachse, who lived at Peter Tork's artistic collective. "David treated women badly, but then, so many guys did."

By contrast, Joni would never be servile, and, according to Salli, David “respected her as a peer.” She was also emotionally "turbulent" -- David's word -- and so, in those first weeks in L.A., it was often left to Estrella Berosini, who'd moved from Florida to L.A. at the same time, to play the little sister buffer and mediate between the two headstrong singers. One night, when they were all driving up to Stephen Stills' house (and David and Joni had unaccountably broken out into a chorus of "Abba dabba dabba dabba dabba dabba dabba, goes the monkey to the chimp"), David came down hard on Joni for her expensive purse. While they were still in Florida, he had gotten her to scrub off her Carnaby Street-style eye makeup in favor of the natural look; now he wanted her clothes to be more hip and funky, less discotheque-y. "That's the right purse!" he'd said, pointing to Estrella's raggy fabric pouch (while Estrella longed for Joni's handbag, "which she probably bought on Madison Avenue"). "You know, Estrella," Joni said to her young friend, one day during those early weeks in L.A., "I really do love David, but when we get together, we just don't get along."

Still, there existed no more heartful trumpeter for Joni's arrival in L.A. than David. He presented Joni like a showman. One night, for example, he lured members of the San Francisco-based theater group The Committee up to a house in the Canyon, where, as he and memoir co-author Carl Gottlieb described it, "a half dozen stoned and lucky actors heard a never-before-recorded Joni Mitchell sing half her new album in the predawn light. The company was stunned." One of them apparently said: "`We thought we halluci- nated her.’" David’s account sounds exaggerated, but Leah Cohen Kunkel, the sister of Cass Elliot and the new wife of a young drummer up from Long Beach, Russ Kunkel, says it isn’t. “When Joni would sing over that guitar, men were riveted – they stopped what they were doing, they were absolutely enamored. Before that it was always women [in the canyon] riveted by the male guitarist – this was the first time it changed. Joni got introduced to the cream of the pop rock world, and she was accepted right away.”

Russ recalls the new-to-the-Canyon Joni this way: “Most of the women there were pretty magical then ‘cause there was this incredible feeling of freedom that was enhanced by various things, including drugs, but Joni was drop-dead beautiful. And she had this amazing voice: her voice register and her guitar tunings, which no one had heard.”

Joni recorded her first album Song to a Seagull, which, in subsequent pressings, came to be known, merely, as Joni Mitchell, in the first weeks of 1968. David had himself named producer of the album; Joni termed him its “conservationist,” holding the line against those who might complain that she'd "had a whole paintbox and use[d] only brown." In reality Joni was in control of her product, an unusually nervy move for a newbie on her maiden voyage with a major record label. She kept the album acoustic and intimate: just Joni and her guitar. The album may have suffered from the spareness, for it had an astringent forlornness and never got past 189 on the Billboard chart.

The album cover was a painting by Joni. Her psychedelic mélange of voluptuous flowers, in orange, green and yellow, enclosed a fish-eye-lens photograph of her standing on a dark, trash-can strewn New York street, dressed for winter, carrying her belongings, hoisting an umbrella over her head. Her sketch of Crosby's boat was off to the right, under the words SONG TO A SEAGULL, etched brokenly by a flock of gulls. Amid the painted flowers -- petals opening from stamen -- were two almost anthropomorphic cacti, for her alter ego, the cactus tree. Joni dedicated the album to Arthur Kratzmann, the seventh grade teacher who had mercilessly scrawled "Cliché! Cliché!" all over her essays until she finally learned to write with originality.

The songs introduced listeners to veiled snippets of the life of this still very-unknown singer. In "Part [side] One: I Came To The City," there unfolded, in this order, her marriage-gone-wrong to Chuck in "I Had a King"; her affair with Michael Durbin in "Michael From Mountains"; the joyous "Night in the City," her touché to the small-minded moralists who'd looked on the Yorkville folksingers (including that poor, pregnant one) as degenerate hippies; and, finally, with "Marcie" and "Nathan LaFraneer," her testimony to the trials of a young woman alone in Manhattan. She named the B side "Part Two: Out of the City and Down to the Seaside," making her meeting of David in Florida into a kind of deliverance -- which, in career terms, it was. "Cactus Tree" is the stem-winder on that side. Joni’s atypically rousing guitar intro, a change of pace after the more melancholy fare, creates the impression that she’s bounding out from behind a curtain, ready to present this female-triumphal anthem as an encore to a worked-up audience. At least that’s how it sounds now, with almost forty years’ hindsight.

The reviewer for Rolling Stone was breezy – “Here is Joni Mitchell. A penny yellow blonde with a vanilla voice….a lyrical kitchen poet” -- but ultimately respectful: He duly noted her reputation among folk music followers and her excellently recorded songbook, but he couldn’t quite get excited. “The… album, despite a few momentary weaknesses, is a good debut,” he concluded.

The album had been initially put at risk by a tape hiss that was audible only after all the tracks were laid down. A worried David Crosby had driven the tapes to the Laurel Canyon house of Elektra sound engineer John Haeny. “The tapes were a mess,” Haeny has said. Slipping into the studio, he remixed Joni’s album, rescuing it.

Around this same time, Haeny awakened in his Ridpath Lane house one morning to “some chaos” and found Judy Collins, nude, amid a tangle of yellow flowers at the wooden fence in his yard. Judy was a friend, and she was having herself photographed for the cover of the Joni-song-filled album Wildflowers. Judy had recently broken up with rock writer Michael Thomas, so Haeny introduced her to his friend Stephen Stills, who proved a good match for the tempestuous Collins. A military-school-educated boy who grew up in Florida and Louisiana, Stills was conceited and combative (some used the word “obnoxious”), and – with his sleepy-lidded blue eyes in a wide, high-foreheaded face framed by mutton-chop sideburns and wispy blond hair (and despite -- or maybe with the help of -- his terrible teeth) – very sexy in a young-Steve-McQueen kind of way. Had many people known that he’d auditioned to be part of The Monkees, some of his edgy charisma may have evaporated. Just before the Collins-Stills match was made, another, interlocking connection was struck during Joni’s recording sessions. In the adjacent studio, Stills and the Buffalo Springfield were recording; one of Stills’s group-mates was Vicky Taylor’s good friend from Toronto, Neil Young. Stills, who was (of course -- wasn’t everyone?) a friend of Crosby’s, ended up playing bass guitar on “Night in the City,” the only outside musician (except the banshee player) to intrude on Joni’s solo performance. Joni introduced Neil Young to Elliott Roberts, thinking their humor made them kindred spirits, and Roberts became Young’s manager, too.

Completing this new musical circle was a gentle English rocker who would become one of the great loves of Joni’s life.

Graham Nash was, as he says, “a poor man’s son,” from Blackpool, England. When he was fourteen he’d wanted nothing more than to use his voice and guitar to make others feel like he felt when he listened to the Everly Brothers. He and his friend Allan Clarke had formed The Hollies and, with the group, were part of the British Invasion. “Carrie Anne” and “Bus Stop” were more-than-likeable hits– the former, fetching; the latter, dark – in 1966 and 1967, the twilight of formula English pop. Nash, who was one year older than Joni, had been married young, and was divorced. He was a tall, thin, approachably handsome man with intense, closely set eyes in a narrow face framed by a rich mass of shaggy dark hair, and he had a manner both gracious and intimate. In his travels to Laurel Canyon, he’d struck up a close friendship with Cass Elliot, to whom he found it com-fortable to pour out his heart out. He was a romantic and an appreciator. To him, Laurel Canyon was like “Vienna at the turn of the century or Paris in the 1930s.” But he was edgy, too (what rock star wasn’t?), and he dressed with neo-Edwardian panache. When Joni ran into him at a radio station’s party for the Hollies at a hotel in Ottawa (where they were appearing in a concert hall and she, in a coffee house) shortly after she finished recording her album, “he was very British mod,” Joni has said. He was wearing one of “these ankle-length black velvet coats and yards and yards of pink chiffon, almost foppish, like the way Jagger and a lot of the British bands dressed at the time.”

Knowing they’d be in the same city, David Crosby had given Graham (they’d met through Cass) advance word on Joni. “He’d said, `Watch out for this woman’ – in a good way, that she was very special and very beautiful,” Graham recalls. But Nash had all but forgotten those words when “through the usual lineup of beers and juices, I saw this woman sitting by herself with what looked like a Bible on her lap. [It was actually an antique photo album encasing a music box.] She was something to behold.”

Meanwhile, Hollies’ manager Robin Britten had grabbed Nash’s ear. “He kept talking to me about business,” or so it seemed, “but I just wasn’t there,” Graham says. “My attention – my essence – was over in the corner, with that girl. Then Robin said, `Shut up for a moment! There’s a woman I’m trying to tell you about and you haven’t heard a word!’” “I said, `That’s because I’m looking at this woman.’ He replied, `That’s the woman I’m talking about.’

“So I walked over to Joan and introduced myself, and she invited me to her room in the hotel, and I ended up spending the night with her, and” -- he admits, thirty-five years later (and in the midst of a long, happy marriage to another woman) -- “I haven’t been the same since.” In the dim light of her room at the Hotel Laurier, which gave off on a romantic view of rooftop turrets and the adjacent Parliament building, Joni took out her guitar. “But I loved her before she played a note,” Graham says, “just from looking at her and talking to her and realizing what her spirit was.” For her part, Joni thought Graham “very gentle, soft-spoken and kind, with a certain degree of rock ‘n’ roll arrogance mixed in.”

Joni wooed the already smitten Graham as she had Roy Blumenfeld, Leonard Cohen, and David Crosby – with her songs. Despite her femininity, like a man, she displayed her work to her would-be lovers. “She played fifteen songs, almost her entire first record, and a couple of different ones, too,” Graham says. “By the time she got through `Michael From Mountains’ and `I Had a King,’ I was gone. I had never heard music like that.”

Graham returned to England, but, on the basis of transatlantic counsel from Mama Cass, he began thinking of quitting the Hollies, moving to L.A., and trying to launch himself as a solo act. He had already written the bouncy, quite-wonderful “Marrakesh Express,” about the trend that the English rich hippies had started -- and American counterparts would soon pick up -- of traveling to that fabled souk-laced city in Morocco and paying a court-visit to Ahmed the wacky, notorious “King Hash” in his rug-smothered lair.

Meanwhile, Joni continued her Canadian tour and struck up a platonic friendship with Jimi Hendrix, for whom she opened at a subsequent engagement in Ottawa. Like many women coming upon Jimi in private, Joni found him to be the startling opposite of his reputation. He was “sensitive, shy, sweet,” she’d recall-- and obsessed with getting away from what she called the “phallic” aspects of his performance. (Writing in his diary, Jimi called Joni a “fantastic girl with heaven words.”) After the evening’s show, Joni, Jimi, and his drummer Mitch Mitchell stayed up late, talking and playing in one of their rooms. It was all “so innocent, but the management-- all they saw was three hippies,” she later railed, angrily. “A black hippie! Two men and a woman in the same room!”

After her tour, in the spring of 1968, Joni bought a house in the canyon, a romantic aerie with wide plank floors, broad-paned leaded windows, and wood-beamed ceilings at 8217 Lookout Mountain. It was close by Carole’s house, but the two women did not know one another. The house was built in the 1920s, right into the side of the mountain, “so when the trees spread out,” Joni has said, “the branches were right at the window; birds flew in and nested.” Joni filled the house with antiques, quilts, and flowers, and she set her guitars on her Priestly piano. A Tiffany lamp and stained glassed window panels caught the canyon sunlight, which, of course, poured in like butterscotch.

In July, Graham moved to L.A. and moved in with Joni. "We were both pretty terrified of a deep relationship," Graham says, but they slipped into one anyway. "I'd been divorced--both of us had-- and I knew she was a little skittish about [commitment]." Joni's family history was not far from her mind. "She didn't want to be like her grandmothers," Graham says. "They had given up artistic careers to take care of husbands." That lesson was "always an unspoken thing between Joan and me."

One night, shortly after Graham moved in, David and Stephen came over to Joni's. The ex-Byrd and the Springfield member had been spending days writing and singing together. For all his rock-bad-boy panache, David was a folkie at heart – he’d originally had trouble playing his guitar while standing, rather than sitting, and his bottom tenor was luminous. As for Stills, it was his scratchy, bluesy voice that had made the Springfield's "For What It's Worth" a radical political battle cry.

Stephen had penned a song, "You Don't Have to Cry," for Judy Collins, whose high-powered career was pulling his macho nose out of joint. "In the morning, when you rise," the song asked, "…Are you thinkin' of telephones / And managers and where you got to be at noon?" (Stills's "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes," would be his swan song to her.) Both Crosby and Stills had heard kudos for Nash's high harmony from everyone from Cass Elliot to the Lovin’ Spoonful’s John Sebastian; but they'd never tried to sing with him. Sitting around Joni's living room, getting high, Stills and Crosby sang the first bar of the new song: Crosby the tenor, Stills the alto. Nash asked, "Would you sing that again?" Stills and Crosby repeated the bar. Nash listened intently and, again, asked them to sing the line. When they did, he queried a third time. This time when they reprised the bar Graham chimed in, producing a straining, poignant, slightly sour top-note that lifted the song to an ecstatic new dimension. "All four of us -- the three of us fellows and Joan -- knew! It was a truly amazing moment."

Crosby, Stills and Nash would become a phenomenon -- three stars of three different groups, each contributing beautiful songs (Stills's two for Judy Collins; David's rich-hippie dreamscape "Wooden Ships" and his elegy for Bobby Kennedy's murder, "Long Time Gone"; Graham's "Marrakesh Express" and his ode to his domesticity with Joni, "Our House") to their eponymous album, sung in their piercing harmony. But it would be a song of Joni's-- one of her finest and most sociopolitical -- that would fully introduce Crosby, Stills and Nash to the nation and would give them their signature hit: a hymn to the capstone cultural event of their generation’s decade. That would come a year later.

Graham adored Joni, and he made no secret of his awe of her. "There was always this edge of me looking at Joan and thanking my lucky stars," Graham admits today. "I felt a little like, `What the fuck am I doing here, with this woman? This woman loves me? This is insane!' I looked at Joan as a goddess, and she was." He called her Joan (her subsequent boyfriends would, as well); she called him Willy, the diminutive of his middle name. Did Joni recognize her power over men? "I don't think you can have that power and not recognize it. Did she utilize it or abuse it? Absolutely not. But you can't be that beautiful and talented and not know that guys are falling for you, right, left, and center."

Joni and Graham would race each other to the piano after morning breakfasts at Art's Deli in Studio City. "It was an intense time," Graham has said. "Who's going to fill up the space with their music first? We [were] two very creative writers living in the same space, and it was an interesting clash: `I want to get as close to you as possible.' `Let me alone to create!'" Those songs of Joni's that are clearly or presumably about life with Graham reflect that push/pull of intimacy, in lyric styles ranging from biblical reverence ("Sometimes in the evening / He would read to her /Roll her in his arms /And give his seed to her," in the achingly lovely "Blue Boy"), to Nashville-worthy wit ("But when he's gone, me and my lonesome blues collide / The bed's too big, the frying pan's too wide," in "My Old Man").

"We'd make love, often, in her tree house," Graham volunteers. "We'd do crazy stuff. Once, we went to New York, and we saw these kids who had opened a fire hydrant. We got out of the limousine and into the spray of the hydrant, and then we got back into the limousine, completely soaked." During this or another trip to the city, they ran into Gene Shays, the Philadelphia deejay, at a drugstore in Sheridan Square, and Shays was touched by how Graham "gallantly" kept guard in the aisle so that no one would see Joni purchasing sanitary napkins. Graham's decorousness is reflected in the opening line in his "Our House" -- "I'll light the fire, and you place the flowers in the jar that you bought today." Respectively Canadian and English, both from Queen-loyal, tea-sipping, lower-middle-class Protestant homes, they were, to each other, known quantities within a swirling rock-world ethnic melting pot. For Joni, Graham was a natural mate and a resting point. His talent was overmatched by hers, but he knew it and his humility made him charming. He saw her turmoil: "She was vulnerable, lonely inside, and angry, even though she was surrounded by people who loved her," he says -- and it echoed his own vulnerability. "I had never been so much in love. I had never been so unsure of myself. I had never been so fragile." Yet, "People would say we would light up a room when we walked in," he says today. Perhaps it was the fragility shining through their confidence and glamour that made them evanescent.

Joni did not tell Graham about her baby right away. "When you're wooing a new lover, you don't say, `By the way, I've got this kid I gave up for adoption'." But when she did broach the subject, she spoke of the pain of the “shame and guilt and wanting a life” and of the "rejection" she knew she would have faced from her parents had they known about the birth. She recalled her ordeal, describing it all with still-fresh emotion, and blaming Chuck -- a version of events she had now settled into. Graham felt the surrender of the baby “was devastating for her. It had a tremendous effect on her emotional growth."

Joni began to spot her daughter, at music festivals. "At concerts, she would see a little girl's face, and she would wonder," says a friend from those years, Ronee Blakely.

The first Kelly sighting was at the Big Sur Folk Festival that summer.* "We thought we saw her daughter," says Graham, for he, too, having absorbed her emotions, believed it. "There was a sound check before a communal early dinner. We lined up to get our food. And I remember this young -- eight or nine year old -- blond girl in line, waiting to go to dinner. The little girl said, `Who are you?' Joni said, `I'm Joni Mitchell.' And the little girl said, `No, you're not; I'm Joni Mitchell.' And then Joan looked at me -- it was one of those strange, Twilight Zone things -- and then the little girl disappeared." Of course, in 1968 Joni's daughter would have been three, not eight or nine. But the incident reveals how fixated Joni was on the loss. Graham believes: "Joni's daughter has haunted Joan since the moment she gave her up.

Shortly after Big Sur, Joni flew 3,000 miles northeast and attended the Mariposa Festival. There, she had another encounter with a little girl, closer to Kelly Dale's real age and closer to her likely home now. As Joni later recalled, she and the other performers were corralled behind a fence, but a festival representative came to fetch her -- there were some people who wanted to have a word with her. Approaching the fence, Joni saw a young couple. The man had a little boy on his shoulders; there was a little girl (who Joni judged to be about three) beside them -- "a small, curly-haired blond girl -- my child had thick, thick curly hair," Joni noted (apparently referring to her memory of the several-months-old Kelly Dale in the foster home). The child's fingers clutched the fence's chain links. "I looked at [the family]. Nobody spoke. Nobody spoke until the child spoke. And she said to me, `Hello, Kelly.'" "And I said, `My name's not Kelly. My name's Joni.' And she said, `Nooo….No, you're Kelly.'" The mother warmly intervened, explaining that the little girl's name was Kelly. But the child herself continued insisting that Joni was named Kelly. Joni believed the child was trying to tell her: I am your Kelly -- your Kelly Dale -- and you are my mother.

Joni asked the parents: "Do you have anything to say?" They didn't, and they walked off. Did the encounter really happen that way? Or did Joni part-imagine it? For twenty-five years Joni "always suspected" that that curly headed girl at Mariposa was her daughter.

In fact Joni's daughter went nowhere near a folk or rock concert, during those first three years of her life (although she did live near the Mariposa site, in a Toronto suburb called Don Mills, and she did have a brother). Her adoptive parents, schoolteachers David and Ida Gibb, were earnest and introverted: book people – the last people one would expect to find at a pop or even folk concert, says one who knows them. David had been born in Scotland and migrated to Canada with his parents as a boy; Ida was of Ukrainian descent and grew up in Winnipeg. The Gibbs's biological son, David Jr., was four on the September 1965 day that Joni's seven-month-old baby Kelly Dale was officially named Kilauren Gibb. (The similarity between the names "Kelly" and "Kilauren" -- the latter, chosen to honor David Gibb's Scottish heritage -- is coincidental.) According to a man who grew up with Kilauren Gibb, shortly after the baby arrived, David Jr.’s parents took him aside and told him to never tell his little sister that she was adopted. Infant pictures of David Jr. were swept off the tables and walls so the lack of infant pictures of Kilauren wouldn't seem odd. David Jr. was blond, like his adopted little sister; they looked enough alike to be natural siblings through early childhood. Still, by summer 1968, when Joni was experiencing these cryptic encounters with little girls, members of the Gibbs' Donalda Country Club were beginning to wonder how the beautiful little spitfire could have been born of two cautious, not-very-attractive parents. Every passing year, a few more people in Don Mills would speculate if Kilauren Gibb were adopted. Her parents would always, adamantly, tell her, No! You are our natural-born daughter.

Joni began work on her second album, Clouds, in early 1969. A sound engineer with an interest in Buddhism, Henry Lewy played producer on the effort, in the same “beard” role that David had, on her first album. Again, Joni was in control. This time she used guitar accompaniment only (on Seagull, she had also played piano). For album cover art, she painted a super-realistic portrait of her face: hair streaming over a black turtleneck, she is holding up a bright red, too-widely-open-petaled flower, pointing it at the viewer, at whom she is staring. The exaggerated tips on the petals match the exaggerated tips on her tightly closed lips. The message is one of great self-exposure and great rectitude, all wrapped up in feminine symbols. Behind Joni was the Saskatchewan River -- yellow clouds broodingly descending into the dark water-- with the medieval turrets of the Bessborough Hotel on the far shore. She dedicated the album to her grandmother, Sadie McKee, whose legacy of frustrated creativity she was expressing. The confrontational self-possession was almost groundbreaking, "almost" because, by now, Laura Nyro had raised the bar for female confessional songwriting, a genre she had virtually invented. (Joni would meet Laura in a few months, by way of their mutual manager, David Geffen. They would admire each other’ music.) But Laura Nyro's songs were now almost hysterically vulnerable and esoteric. Her Eli and the Thirteenth Confession and imminent New York Tendaberrywere tender, frantic operas, full of leaps and hints and dream-shards; a listener either got Laura's plotline of a female naïf baptised by the sanctifying rough-play of soulful life, or was so overwhelmed by the passion that she took it on faith. Joni's songs were more conventionally melodic and satisfyingly narrative.

Two of Joni's songs on Clouds were for Leonard Cohen -- "Song About the Midway" and "The Gallery." There was also "Tin Angel,” in which a woman is surrounded by the accessories one would imagine in the antique-bed boudoir that she had described at the Second Fret: measuring her soothing mementoes against the insecure love of a "sorrow"-eyed man. She added her most iconic songs -- "Chelsea Morning" and then, as last track, "Both Sides Now," which she'd finally stopped hiding behind -- Judy Collins's lusher, accessible covers of which declared that Joni was, first of all, a writer. Her mournful "Songs for Aging Children" would soon be included in the Arthur Penn-directed antiwar movie of Arlo Guthrie's song, Alice's Restaurant. "I Don't Know Where I Stand" gave listeners the cactus tree, de-spiked and humbled, feeling her way through an infatuation so fresh that “even the sound of your voice is so new," with all its self-consciousness and bet-hedging. "I Think I Understand" --full of Child Ballad hoariness -- paid homage, like "Urge For Going" had, to the form her own songs supplanted.

A Carnegie Hall concert on February 1, 1969 announced Joni as a celebrity. Her parents flew down from Saskatoon and stayed at the Plaza. Backstage, Joni stood with Graham, who looked suitably rock-star-foppish, in her thrift store felt skirt with sequins in the front and giant artichoke and American flag appliqués. Myrtle, aghast, said: "You're not going onstage at Carnegie Hall wearing that, are you?" Bill Anderson placated his wife. "Oh, hush, Myrtle, she looks like a queen in those rags," he said, as their daughter took the stage for the performance that would earn her a standing ovation.

At her next concert, in Cambridge, a month later, a lanky, handsome unknown with deep-set eyes, long brown hair, and a thin mustache opened for her. He played a song he'd written, "Something in the Way She Moves," and when he got to the words "my troubled mind," his nasal-voiced melancholy hinted at a real troubled mind, though his well-bred manner belied all his brooding and slumping. The song had been included, along with Joni's "Circle Game" and "Tin Angel," on Tom Rush's album Circle Game. His name was James Taylor, and he was back in America, after his making first Apple album, dividing his time between his family's Martha's Vineyard home and L.A., where he would soon start recording his second album, Sweet Baby James. He was hanging out with Kootch's crowd. James came back to Joni’s dressing room and said hello. But she was involved with Graham Nash, and he with Margaret Corey.

Meanwhile, the fan base Joni had first found in her post-Chuck-and-Joni concerts was gathering number. Clouds would betterSeagull's Billboard standing by half (it charted at 93). Joni's face -- framed by her waxy blond hair; sporting a wary, sideways expression, her long, manicure-nailed hands forming a little teepee in front of her lips --filled a Rolling Stone cover in May, accompanying an article that began: "Folk music, which pushed rock and roll into the arena of the serious with protest lyrics and blendings of Dylan and the Byrds back in 1964, has re-entered the pop music cycle." The review ended with, "Joni Mitchell has arrived in America."

Significantly, the article mentioned that Joni "shares a newly purchased house with Graham Nash." This, of course, was Rolling Stone -- not a “straight” magazine like Life. Still, in mid-1969, a tossed-off reference to "living together" announced an avant garde state. Choosing to cohabit out of wedlock with such thoughtful, romantic gentility as Joni and Graham were applying to their lives (the article took note of Joni's "antique pieces crowd[ing] tables, mantels, and shelves,.…[her] antique handbags…on a bathroom wall, a hand-carved hat rack at the door…castle-style doors…a grandfather clock," and mentioned that, during the interview, Nash was "perched on an English church chair" while Joni was "in the kitchen, using the only electric lights on in the house…making the crust for a rhubarb pie") elevated the seedy state of cohabitation to elegance and proved you could get the piety of the wedding-in-the-woods -- without the wedding. Increasingly, young middle-class-turned-hip women were choosing to “live with” their boyfriends, not marry them. You had to have a name for your living-withee, so, to cut against the elite sweetness of the lifestyle, gruff working-class terminology was appropriated: "My old man," "my old lady." Joni's wrote "My Old Man”to legitimize this phenomenon and to locate herself and Graham within it; Graham’s “Our House” seconded the motion.

Being someone's Old Lady was a proud sign of emotional security (a young woman didn’t need marriage to feel that she was not being taken advantage of by her boyfriend) and it was the expression of a new – negative – way of viewing the institution of marriage. It wasn't just the guy who liked things fine the way they were, who (as the crass saying went) wouldn't buy the cow now that he'd started getting the milk for free, while the girlfriend longed, and lobbied, for commitment. Rather, it ws the girl who now disparaged marriage in her own right, out of idealism and anti-authoritarianism. Joni presented the argument, in folky dialect: "We don't need no piece of paper from the city hall, keeping us tried and true" ("and we did feel that way," Graham says. "We didn't need to get married to feel that way"). Living with a man without a wedding license had always been considered low-class (“common-law” marrages were for common people), desperate, morally shady – or all three. Now, the choice to live in a situation that included sex but not a wedding license was a mark of enlightenment for a young woman.

Crosby, Stills and Nash had cut their album, and the atmosphere in the studio had been giddy. "It was scary; once we knew what we had, you could not pry us apart with a crowbar; we knew we'd lucked into something so special, man," Crosby said, of their aural combination. And Joni said, "The feeling between them was very high, almost amorous. There was a tremendous amount of affection and enthusiasm ….Part of the thrill for me being around them was seeing how they were exciting them- selves mutually. They'd hit a chord and go, `Whoooaa!,' then fall together, laughing."

"Joni was one of the boys," Graham says. "She would have picked up a basketball and shot hoops. It wasn't that we were in a club that she needed inviting to. It all came naturally." She accompanied them to rustic Big Bear to shoot the inside photographs of Crosby, Stills and Nash. In pictures from the day, she’s in the back of the limo between dapper, mustachioed David and handsome, scruffy Graham: demure in a cap-sleeved sweater, a cross dangling on a chain around her neck -- the hippie-schoolgirl hair she helped make fashionable--bangs down to the eyebrows; straight hair streaming, topped by a knit cap. She kisses a delighted-looking Graham's hand as she pens a lyric for a song about him, "Willie" on a notepad: "Willie is my child, he's my father / I will be his lady all my life."

In mid-August, Joni and Crosby, Stills and Nash (now with Neil Young, with whom they would record their next album Déjà Vu) flew to New York to appear on the Woodstock Music and Art Fair, and for her booking on the prestigious Dick Cavett Show, the night after the festival. By now she had opened for her boys at several packed concerts, and the huge fan reaction had proved that three (now four) male rock stars were exponentially more charismatic than one female folksinger.

Woodstock, "Three Days of Peace and Music," was a festival planned for August 15, 16, and 17 in Bethel, New York, at $18 to $24 for the entire three days. Two promoters in their early twenties, Artie Kornfeld and Michael Lang, backed by a twenty-six-year old financier named John Roberts, wanted it to be the biggest rock festival ever. They had duly emptied their pockets, doubling Jefferson Airplane's going $6,000 fee to $12,000, and paying Jimi Hendrix, now the biggest rock star in the country, $32,000 (his mana- ger had asked for $150,000 but settled on the smaller figure on the condition that no act follow Jimi). Woodstock would feature the most glamorous, top acts --Janis Joplin, Jefferson Airplane, and Richie Havens (who would open the show); Jimi Hendrix, who would close it, providing, from the depths of a soul torn between erotic showmanship and an embrace of aboriginal New Music, the most dramatic “Star Spangled Banner” in recent history; the Grateful Dead, the Who, Joan Baez, Country Joe and the Fish, Tim Hardin, the Band (becoming the group, by way of their quirky Canadian-cum-deep-South roots, fresh-from-the-Civil-War sound and adoption by Bob Dylan), Ravi Shankar, Blood, Sweat and Tears (these were Joni's Blues Projects friends -- Steve Katz, Roy Blumenfeld, Al Kooper – and soon: British belter David Clayton-Thomas), and tomorrow's stars: Sly and the Family Stone; Santana; Credence Clearwater Revival.

Throughout Kornfeld and Lang's negotiations with the town of Wallkill, New York, they continued to insist that a crowd of, at most, 50,000 would be attending. But, given the aggressive promotion the festival was receiving in Rolling Stone, The Village Voice, The New York Times, and on the radio, the townspeople doubted the numbers would stay that low. A month before the festival, the town of Walkill abruptly rescinded its offer.

The promoters looked for a savior -- and they found one in Max Yasgur, the biggest dairy farmer in the valley and the holder of an NYU law degree. Yasgur offered his 600-acre farm for $75,000, even though, with the crowd-count now whispered to be an astonishing 200,000, extensive trampling seemed likely. The promoters enlisted the Hog Farm, the country's most famous commune, led by ex-Cambridge folkie Hugh Romney (an old friend of Joan Baez and Betsy Siggins), who now called himself Wavy Gravy, to bestow back-to-the-land authenticity and to provide infrastructure: security, food stands, shelter, a "free school" for kids. Wavy Gravy called his cross-country counterpart Ken Kesey at his commune in Oregon, and dozens of overalls-clad, acid-tab-bearing Merry Pranksters were promptly dispatched east in psychedelic school busses.

The divide between young / hip and old /straight had been around since 1966’s Human Be-In in the Haight Ashbury, and it had been celebrated with every smoked joint, every dunking of a knotted cotton T-shirt into a tub of Rit dye, every raised two-finger peace sign. It had taken three years for the lifestyle’s tentacles to stretch to the vast domain of American middle class youth, and now that that it had, a Haj to a Mecca seemed in order. Where Monterey Pop had been the hip elite--a jazz-concert’s savvy crowd of fans close to the age, taste, and coolness level of the performers--Woodstock would be hip democ- racy: wildly enthusiastic college kids, working- and middle class hippies, and drug-brined riffraff. Where Monterey Pop had been a bellwether boutique, Woodstock would be Wal-Mart. As Arnold Skolnick, the artist who designed the festival's catbird-on-guitar logo put it, "Something was tapped -- a nerve -- in this country. And everybody just came."

As Joni, Graham, David, Stephen and Neil were preparing to fly to New York, the Bethel town elders neighbors were angrily hectoring Yasgur to give back the money and keep the hippies from overrunning their orderly town. But Yasgur held firm to his agreement, even as reports shot through the news that 800,000 people -- sixteen times the original maximum estimate -- were on their way there.

Joni wanted to perform, but Elliot and David Geffen were fearful for her safety. Besides, even if she got to the festival safely, would she get back in time for the Cavett Show, the next night?* The festival had already started; the round-the-clock perfor- mances were a half-day or more behind schedule; traffic was blocked for twenty miles; many festival-goers had left their cars on the highway or sides of the streets and, truly like pilgrims now, were walking. The stars were being airdropped in by army helicopter.

The boys hired a small plane to fly them into the festival; Joni went to Geffen's apartment and, from the point of view of "the girl who couldn't go to the party," watched it on TV. "The deprivation of not being able to go," she has said, "provided me with an intense angle on Woodstock." That longing showed up in the song she wrote.

Ultimately, some 450,000 exhuberant souls came to the festival, to withstand the rain and mud and the inadequacy of facilities (there were only 620 portable toilets) with joyful brio. Street signs sprouted up: Groovy Path, Gentle Way, High Way. People made love and shared food, tents, acid, dope, bandaids, water, blankets. A couple of babies were born. Three people died, and 400 bad acid trips required medical attention, but no violence broke out. Swami Satchidananda wafted in and gave the crowd his blessing. Max Yasgur (suddenly the biggest rock star of all) intoned to the mike, "This is the largest group of people ever assembled in one place, and I think you people have proven something to the world: that a half a million kids can get together and have three days of fun and music and have nothing but fun and music and God bless you for it!" Joni, who had been feeling religious of late, felt that what she was watching on TV was "a modern miracle, a modern loaves-and-fishes story. For a herd of people that large to cooperate so well, it was pretty remarkable -- there was tremendous optimism." She also viewed the spectacle through the eyes of a girl from a long line of farmers -- Yasgur (she would cite his name early in her song) had done all farming-folk proud, including her grandparents. Joni wrote her song about the raucous weekend in counterintuitive minor mode; it had a primordial, dark-Edenic / Nordic winter-forest sound, with Biblical echoes that started with the first line "I came upon a child of God; he was walking along a road" and were dotted throughout ("the garden," "the time of man"). The mirage of "the bombers riding shotgun in the sky" -- she conflated the peaceful helicopters soaring into the meadow with the military craft of the Vietnam War -- "turning into butterflies across our nation" held the naïve hope that fueled the day. But it was the first line of the chorus -- set to those spectral, pessimistic chords -- that made the song so hauntingly elegiac and conveyed the impression of hundreds of thousands of people speaking as one. Years later, cultural critic Camille Paglia, in her book Break, Blow, Burn, would feistily place the lyrics to "Woodstock" along with works by Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath, Emily Dickinson -- and Shakespeare -- on her list of 43 best poems produced in the English language.

By the time the boys got back –talking of how they'd commandeered a pickup truck with Jimi Hendrix to get from the airfield to the festival tent and how they hadn't performed until four in the morning-- Joni had completed the song. She’d intuited the significance of Woodstock from her armchair. "[Joni] contributed more towards people's understanding of that day than anybody that was there," Crosby has said, of the song that, in rock version, he, Nash, and Stills would make into their defining hit.

Within days, back in L.A., Joni opened for her boys at the Greek Theater. If there had been doubt as to where she was now positioned in relation to this male group she'd helped ignite, it was banished by Los Angeles Times critic Robert Hilburn, who called Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young's performance "a triumph of the first order" and said that Joni's performance had been "overwhelmed" by theirs. She may have been beginning to wonder: What was the price of being someone’s Old Lady?

On the one hand, being an Old Lady -- or a “Lady,” the kind of arty, sensual, esoterically spiritual chick for whom the coolest men had lust and awe -- well, you couldn't beat that. All over the country, young women were trying to shoehorn their personalities into that fashionable archetype: Talkative girls got stoned and talked slower. Unaesthetic girls took to wearing dangly jewelry; pragmatic girls started reading their horoscopes. Verbal, argumentative girls pretended to be anti-intellectual and serene. But many young women (especially, it seemed, in Laurel Canyon) didn’t have to try, didn’t have to change themselves; they personified this contrarianly glamorous new young-womanliness. For example, there was Annie Burden, the wife of architect-turned-album designer Gary Burden (he'd designed Crosby, Stills and Nash), standing at the door of her house near San Vicente, proferring delicious organic treats with a kid on her hip. Then there was David’s pal Trina Robbins, the comic-book artist and designer who made clothes for Cass Elliot, Donovan and Jim Morrison’s girlfriend Pam Courson; Trina’s lace-trimmed velvet mini skirts had been all the rage in the Canyon two years before, and, with her long blond hair streaming over her wide-shouldered thrift-store skunk coat, she was a hippie version of a 1940s movie star. And let’s not forget Joni's kid-sister-like Estrella -- she of the blues riffs and the savvy with elephants, who was often "sailing ships and climbing banyons": there was adventure in that circus girl's bones!

Joni turned the three into her “Ladies of the Canyon,”* according a verse to each. The antiquated-sounding term that Joni coined gave a just-right handle to the now-flourishing feminine style that she herself had helped establish. On the other hand, medieval courtliness had its blowback: When you were someone's Old Lady, a piece of you belonged to your Old Man -- and he was always coming out ahead, because he was a man. David was madly in love with Christine Hinton again; he elegized her as "Guinevere" (though one chorus of the song had been written for Joni), and they’d stroll the beaches hand in hand, both of them as long-haired and nude as Lady Godiva. Still, he dominated her. And while there was no dominating Joni, there was this annoying fact: She had written all her songs and had produced her two (soon, three) albums, yet the guys were the headliners. Before long, she would muse this aloud to a confidante: Was she an artist…or a Crosby, Stills and Nash groupie?

As their live-in relationship went into its second year, Graham says, “Joni was very cognizant of the power of men on her life, and its trials and tribulations. Only in talking to communal friends, when we should have been talking to each other, did I find out that Joni thought I was going to demand of her what her grandmother's husband demanded of her grandmother." Almost plaintively Graham insists: "There was no way I was going to ask Joni Mitchell to stop writing and just be a wife!"

However, looking back on that time, Joni has said, "Graham was a sweetheart" but he "needed a more traditional female. He loved me dearly…but he wanted a stay-at-home wife to raise his children." (And Debbie Green, with whom Joni has been close for decades, makes the point, in support of Joni's concerns back then, that, after Joni, "Graham was never with another creative woman.") But, in all this after-the-fact categorization, a question is lost: Did Joni sense that Graham wanted to give up her writing, singing, and performing? Or did she perceive the comfortable domesticity with Graham, in and of itself, as the threat to the edge and the hunger she needed to push herself to her best writing and singing? That is more likely. "Women of Joan's generation raised the bar of how men should treat women and how women should treat themselves; they were the first to say, `I'm not wearin' this bra!' and `Go fetch your own tea!'" Graham concludes today, implying that their relationship may have been a casualty of that process.

In the early stages of Joni's grappling with this Old-Lady-vs.-independent woman dilemma -- in fact, at the peak of her boys' fame, September 30, 1969, the day that Crosby, Stills And Nash went gold -- tragedy struck their circle. Christine Hinton got behind the wheel of David's VW bus to take her two cats to the veterinarian. As she maneuvered onto the highway, one of the cats escaped the arms of her friend Barbara Langer, who sitting in the passenger seat. The cat pounced on Christine, sending her into a collision with a school bus; Christine was killed. "David was completely crushed, and for days he could barely look at Barbara without seething; Christine parents were there, but they had to wait on David to see what how she would be buried," says a friend.

"Want to go sailing?" David asked Graham. Christine had been cremated, and he wanted to toss her ashes into the ocean from the deck of The Mayan. "I had never been sailing in my life," says Graham, "but I knew David was fragile and decided to stick close by him." When David proposed flying to his boat in Fort Lauderdale and sailing to L.A., Graham stammered: "Hey, wait a second. Isn't that on the other side of this...large country?" Indeed, it was; a nine-week sail -- through the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean, across the Panama Canal and up the Pacific -- was hatched. Joni boarded in Jamaica; she watched 1969 turn to 1970 -- everyone's first New Decade as an adult -- on the deck of the schooner. It was on this voyage that Joni first talked to Graham about breaking up, a decision put on hold while they were on the high seas but wrestled for weeks thereafter.

Also aboard was Florida-based folksinger Bobby Ingram (who'd introduced David to Joni) and his wife -- and a young unknown singer named Ronee Blakley. Ronee was a girl from Idaho, who, on the strength of hearing Joan Baez’s "Barbara Allen,” had bolted for a creative life in Northern California. Ronnee attended Mills College, then Stanford, became a political activist, had a romance with the university's radical student body president David Harris (who later married Ronee's hero Baez and was currently in jail for draft resistance), moved to New York, and was now relocating to L.A. As The Mayan cut through the volatile ocean and David searched for the right place to toss Christine's ashes, "Joan and I would ride on this little seat off the aft -- it was like being on a rollercoaster through a canyon of waves," Ronee recalls. "The waves could be extraordinarily high; sometimes they would break on top of us, and we were all greased up with Ban De Soleil, so we'd slip and slide and have to hang on to the cables not to go overboard."

The trip was like the group's song "Wooden Ships" come to life – hippie superstars huddled together, alone on the vast sea with their dreams and their body heat. A hired cook made what Ronee recalls as "grand feasts" as joints were passed, guitars were strummed, and the music that, many hundreds of miles away, was wallpapering U.S. FM radio tinkled, a capella, over the inky swells beneath the starry heavens. "David was a great sailor, and Graham did the celestial navigation," Ronee recalls. "The men took four-hour turns keeping watch all night, and they manned the sails; the women took care of the galley." At one Caribbean dock the ship was impounded and searched stem to stern. But once it passed muster, peace was made and David sang "Mr. Tambourine Man" to the island's suspicious-constables-turned-autograph-seekers.

Ronee got on David’s nerves. The sound of her typing her memoirs on her portable typewriter so irritated him that he tossed it overboard; then she lost her copy of Crime and Punishment and it was found in the bilge, blocking the pipes. But it was that very urgently expressed literary streak in Ronee that would form the basis of her friendship with Joni, which was consolidated after they docked in L.A. "Joni's core was that of an artist, and I was trying to be an artist," Ronnee says. “I carried my weight in the friendship but she was certainly way ahead of me. Whether we were meeting for dinner at Dan Tana’s or running down to Palm Springs, or calling each other on the phone to play our songs, she was an artist, a pure artist: searching and open-minded and sensitive and vulnerable and tough and disciplined. Anything she did or felt went into her work.”

Ronee and Joni listened to Edith Piaf and Billie Holliday records together. They both found Nietzsche inspiring and would comb through Thus Spake Zarathustra for signifying phrases: Joni was struck by "Anything worth writing is worth writing in blood," which had been her critical teacher Arthur Kratzmann’s motto, and she was jolted by the passage where Nietzsche was “scathing,” as she’d put it, toward poets – calling them vain -- but then talked about “a new breed of poet, the penitent of the spirit,” which was what Joni wanted to be. Joni taught Ronnee how to draw, and Ronnee, knowing Joni admired Van Gogh, bought her Dear Theo, Van Gogh's letters to his brother. Many of the lines the Dutch master had scribbled to his sibling had resonance for Joni. "Where there is convention there is mistrust": that was the small-minded Canada she'd fled. "In order to work and to become an artist, one needs love": this justified her concentration on matters of the heart while others were writing political songs. "I want to go through the joys and sorrow of domestic life, in order to paint it from my own experience": this validated her confessionalism. And: “it sometimes happens that one becomes involuntarily depressed": this was happening to her, and Graham was noticing it. Finally, “parents and children must remain one": she had violated this maxim.

Ladies of The Canyon was released in March 1970 (just as Clouds won the Grammy for Best Folk Performance), and it was shot through with idealism and idealization: idealized long skirted ladies, the pitfalls of worshipful love, the chafing between idealistic women and "straight," moneyed men (whose offices bear their "name on the door of the thirty-third floor..."), the inequity between a rock star's wealth and a street musician's poverty, the misguided destruction of "paradise" for the sake of money. Henry Lewy again produced the spare album (with Joni actually in charge), which contained the title cut, and her two odes to Graham -- "Willie" (but with the roles reversed: in the song, the woman is the needier partner) and the haunting "Blue Boy." "Conversation" and "The Arrangement" -- Sondheim-like-literate, emotional, and narrative, as so many of her songs seem to be -- both describe a sensitive girl's affair with a prosperous man who has a superficial wife. "For Free" puts a halo on the shabby "one-man-band by the quick lunch stand" while Joni guiltily notes her musical fame. Joni's big hit from this album (only one of two -- You Turn Me On, I'm A Radio, being the other -- top ten hits in her career), "Big Yellow Taxi," was written during her and Graham’s trip to Hawaii. "They paved paradise, put up a parking lot" was her at her Tin Pan Alley best. "Woodstock," her lovely "Rainy Night Song" for Leonard, and her tuneful "Morning Morgantown" -- quaint-Canada-Joni -- round out the album. The last cut is "The Circle Game," which she had finally stopped hiding.

But still she withheld "Little Green," the song about her baby.

With this album, Warner Bros. finally understood young women’s identification with Joni. They created a full-page Rolling Stone ad, in the form of a story -- “Joni Mitchell’s New Album Will Mean More to Some Than To Others” – about a hypothetical young woman, one “Amy Foster, twenty-three years old and quietly beautiful,” whose Old Man just took off with another chick. Amy is blue, and she’s thinking of getting in her van and splitting. Listening to Ladies of the Canyon together, Amy is consoled knowing “there was someone else, even another canyon lady, who really knew” how she was feeling.

That Rolling Stone ad – with “Amy Foster” planning to up and drive to Oregon, alone -- captured another new reality about young women: They were going on the road -- splitting, taking off on (as the paperback jacket copy of Keroauc’s On The Road had put it six years earlier) “mind-expanding tri[ps] into emotion and sensation…the philosophy of experience and the poetry of being…passionately searching…for themselves.” As Joni would soon sing, in “All I Want”: "I am on a lonely road and I am traveling, traveling, traveling, TRAVELING / Looking for some-thing, what can it be?" The Marrakesh Express, which Graham had made famous, and the circuit of glamorously primitive rich-hippie enclaves -- Ibiza, the middle-sized of the three Balearic Islands off the coast of Barcelona; Matala, Crete, the ancient port on Greece’s Messara Bay; and tropical Goa, on India’s Western Konkan coastal belt -- brimmed with long-skirted young Americans, traveling with girlfriends, with boyfriends, or alone. In this new form of traveling, the travelers went native because they already felt native. These were adventures of the soul and spirit; you dug deep into Third World lore amid a moveable party of other “freaks.”

For females, this meant getting lost in packed, maze-like souks, with angry rug merchants running after you because you’d accidentally bargained too successfully; watching (on acid) someone you’d just made love to break his neck jumping off the Formentera cliff during Full Moon; being the only English-speaker, and in the minority of two-legged creatures, on a steamer on some body of water in the middle of nowhere; barricading the inside of your door in a hotel in Mauritania because the desk clerk, who was banging on it, assumed any solitary western woman guest was a prostitute: none of this suddenly-typical fare was covered in Arthur Frommer’s guidebook.

The ultimate adventure -- nothing could make a girl feel more like Bonnie-of-Bonnie And Clyde was to smuggle hash out Afghanistan or Morocco, often by packing it in girdles and feigning pregnancy. Rolling Stone regularly devoted a two-page section, “The Dope Pages,” to such applauded hijinx, including the story of a young female graduate of U.C. Berkeley (initials: L.C.), who spent a full year muling hash all over the world as a “pregnant” traveler, with hash packed in a girdle: flying from Pakistan to New York via wildly zigzagging, customs-inspector-outsmarting routes that took her to Alaska, Denmark, Brazil, Portugal, and Luxembourg. Today she heads a division of one of the biggest insurance companies in the country and reflects on her youth: “The first thing I’d say is, I should have stayed away from that married junkie musician who used my innocence to make money! But after that I’d have to admit that the adventure taught me skills – about functioning under stress, making split-second decisions, reading behavior, assessing risk, suppressing fear, and thinking outside the box – that have helped me in business and even helped me overcome two serious health crises. Plus, I got to star in my own movie (and, believe me, it was one).”

True to her cohort and time, at just about the time of Ladies of the Canyon’s release, Joni split for the Mediterranean, with a Canadian poet friend named Penelope. "I had difficulty...accepting my affluence and my success," Joni later said, of this period; "even the expression of it seemed distasteful." Escape seemed the answer, so as spring broke on Laurel Canyon, Joni got on a plane to hit the hip road.

In Crete Joni and Penelope drove a mountain road through citrus orchards to a harbor enclosed like a half-curled hand by sandstone cliffs that dropped down to the azure sea. The cliffs housed 1,200-year-old tombs-turned caves, originally the homes of the ancient Minoans. People still lived in them. This was Matala.

The two women rented an apartment in town. One night they went for ouzo at Dephini’s, a beachside taverna, where a wild-eyed, 24-year-old North Carolinan held forth. His name was Cary Raditz. Cary had been an ad copywriter in Winston-Salem and had worked at an art gallery in Chapel Hill in his two post-college years, but after running off to Matala had become a larger-than-life character. Cary had long, curly red hair and a devilish beard. One night he dressed like an Afghan horseman -- in Pakol cap, loose pants, tunic, and sandals; the next, like a Greek shepherd in blouse-like shirt, flared pants, short jacket, and knee-high fisherman's jackboots, with embroidered caskol tied around his brow. A crooked walking stick completed the conceit. In his one year in Matala, Cary had commandeered a cave to live in, had opened a leather shop and began making what he boasts were “the best sandals in southern Europe,” and had taken several murky trips to Afghanistan, barely evading arrest, which heightened his prestige among the hip and druggy expats. "I was an outlaw," he recalls now, “and a self-created sunuvabitch."

Cary was Dephini’s – he was cook, bartender, dishwasher, waiter, and bouncer. He also marketed his sandals there – diners would take their shoes off and Cary would trace their feet on parchment to send them up to his partners in his shop, while he danced around, Zorba-style, manning the oven, the bar, and the cash register

"All these other men were putting Joni on a pedestal, and she didn’t like that,” notes Estrella. “Cary didn’t have the misfortune of seeing her perform – he met her in neutral territory; that’s why she went [to Crete]. She needed life to be harder.”

Actually, Cary Raditz had heard "Both Sides Now." But he wanted to bust Joni a bit. "I had heard that Joni Mitchell was in town, and I saw her with my friends, and they’d get weird -- giddy and silly and kind of obsequious,” says Cary.* He figured he could cut her down to -- maybe even seducible -- size by the oldest male trick in the books: being mean to her.

The night that he saw Joni in the taverna, "I was short with her, I was dismissive of her." During the mass Zorba-style dancing, everyone in the taverna broke their plates. Witnessing the ear-splitting crash of china to floor, Joni – Myrtle Anderson’s daughter, after all-- instinctively took a broom and swept up the crockery shards created by the people in her party. "Joan sweeps the stuff up from the floor-- the plates, the mess -- and brings it to me, helpfully," Cary recalls. "`Here,' she says. `Thanks,' I say, looking her in the eye. And then I throw it all back on the floor.”

A few more days of this back-and-forth ensued, with Cary playing the intriguing bastard, ignoring Joni’s fame and charm. It worked. He says, "One evening Joni came over to my cave." Carrying her Joellen Lapidus dulcimer, she trooped up the sandstone cliff, and, walking through the natural proscenium arch, beheld the gleaming sea. "I was sitting there, watching the sun set” when she turned up, Cary recalls. He showed her around his lair, which was lined with tapestries from his travels but had no indoor plumbing. His bed placed over an ancient burial crypt. Sometimes he dug into the sediment and unearthed human bones; he'd stuff them with herbs, thyme, and rosemary, dry them out and make them into chillums to smoke hash in, like he was doing now. It was perilous to descend the cliff at night. So they didn’t descend the cliff that night. Joni stayed with him.

“Joni and I got to know each other. We were drunk. We talked about a lot of things. Her music. How she had become a qualified studio technician over the course of her three albums, and she was proud of that. She was concerned with her life. It was shifting. We talked the importance to her of being an artist and relationships.” Joni had left the world of fame and touring, she told Cary, because “she did not like getting patronized, cheated and screwed over by the music industry. She understood the trap of catering to the demands of the audience such that you become a branded product. She was always moving, perhaps to escape becoming a thing.” In this and later talks, the subject of “Little Green” came up, as it now did with all her confidantes. She told Cary about the Mariposa sighting. “She said that she regretted giving the baby up for adoption, but what was she going to do?”

A few days later, Graham Nash was laying a new kitchen floor in the Lookout Mountain house when the doorbell rang. It was Western Union. Joni’s Old Man took the telegram from Greece, tore it open, unfolded the piece of paper with its pasted strips of jagged type, and beheld a single sentence: “If you hold sand too tightly, it will run through your fingers.” Graham’s heart sank. “I knew right away -- it was over.”

That night, Graham sat down at Joni’s piano and wrote “A Simple Man,” with straightforward lyrics: “I have never been so much in love and never hurt so bad at the same time.” In answer to the worry (and accusation) that Joni had voiced, he said: “I just want to hold you, I don’t want to hold you down.” But perhaps at this time in her life Joni was simply unhold-able. And that was a new thing for a young woman to be.

Joni moved into Cary’s cave and stayed for five weeks, gaining weight on his “good om-e-lettes and stew” and feeling the addictive infatuation with the primitive hippie-expat life. “To me it was a lovely life, far better than being middle class in America,” she would later tell an interviewer.” One time she cooked him oatmeal on his small cave stove, and accidentally used kerosene instead of water. “Worst oatmeal I’ve ever had, “ Cary recalls, “and I’m grateful she didn’t set herself on fire.” Of her enthrallment with him, he says, “You’ll have to ask her why she was attracted to outlaws.” She cheerfully acknowledged (in “Carey” and “California”) that he was “a mean old daddy,” a “red red rogue,” and “the bright red devil who [kept] her in [that] tourist town.”

Joni’s idyll with Cary was not untypical. Guys like Cary Raditz were dotted around the rich-hippie outposts in those dope-running-and-vagabonding years, and young women prone to sweeping up crockery shards found vicarious rebellion through the jolt of their outrageousness. It was cathartic to laugh one’s blues and uptightness away, even at the risk of being ripped off in the process. (In “California” Joni grumblingly concedes that while Cary “gave me back my smile,” he also took -- and sold -- her camera. “Yes, I probably did say to Joni, in my ungracious way, `I can probably sell it,’ when she left me her camera,” Cary admits today. “I was an asshole. I wouldn’t have wanted to be with me.”

Joni left Cary in Matala and traveled to Ibiza, which in 1970 was the international capital of rich hippie swagger. The chalky white Old City rose from the port in fairytale Moorish cliffs, its narrow streets peopled with beautiful young expatriates and travelers of mystical, louche hipness -- sexy, semi-bored, decadent, a few of them, wild-eyed -- who seemed to have congregated through some secret whispered game of Telephone. They all carried, hanging on long, straw strings from their shoulders, big trapezoidal straw baskets, stuffed with pan and queso, as they made the daily rounds: café con leche at Cafe Montesol or Alhambra, on opposite corners of the dusty main drag; later, dinner at the vegetarian Double Duck, whose owner knew Mick Jagger and the young Aga Khan’s new bride. At night they carefully segregated themselves from the hoi polloi -- fresh-off-the-ferry backpackers-- at Brooklyn Arlene’s harbor-front La Tierra, where they downed shots of the anise liquer yerbis, then headed home to their rented 400-year old stone fincas in the paradisical Santa Eulalia Valley, to mescaline-trip or snort (and sometimes mainline) cocaine to the strains of Van Morrison’s highly compatible Astral Weeks on battery-run record players.

Joni was the guest of some of these people. But it was through sheer serendipity that she stumbled upon Taj Mahal (whose “Corinna, Corinna” was the second most played song on the island that season). Hearing what she thought was Taj Mahal’s record wafting from inside a stone finca, she knocked on the door -- and there he was, in the flesh. They jammed together, and she would pay him homage in “A Bird That Whistles” on her 1986 Chalk Mark In A Rain Storm. Joni the Celebrity Road Chick came and saw, and conquered Ibiza. But Joni the Sensible Canadian Girl quickly left that neverland; stopped in Paris – so “old and cold and set in its ways” – and, like a homesick, guilty lover (“Will you take me as I am?”) -- returned to what, after five years of city-hopping, she was finally home: California.

One night, shortly after she returned to Laurel Canyon (and Cary had joined her there, courtesy of the first-class Athens-to-L.A. ticket she’d sent him), a spontaneous burst of women’s music bloomed at Joni’s house. Estrella and Joni had been speaking to each other in “prose poetry” – falling into “our creative processes, not interrupting the right-brain hemisphere function, to a point where we spoke in free-form song lyrics,” Estrella says. Friends of Joni’s – other canyon-lady musicians and singers – came over, one by one, Estrella remembers. “There were, like, 25 women in the house; it was this magnetic female jam session. Cary was the only man, practically levitating from all the estrogen.” Joni had already begun writing the songs that would be collected in Blue – “California” and “Carey” and “My Old Man.” She was falling into what she would later call her “emotional descent…when you’re depressed, everything is up for question.” And she was listening with care and interest to Laura Nyro, whose confessionalism was piercing.

Among those in the summer-of-1970 female jam session was another Laura, a Northern California singer and songwriter named Laura Allan, whom Joni had met through David Crosby. Barely out of her teens, the daughter of a jazz trumpeter father and psychologist mother, Laura was part of the Bay Area art and music scene, a kind of corked vial of pure hipness, which, unlike the L.A. and New York scenes, was unsullied by proximity to commercial music enterpreneurs and the cornily anxious straight media. She and her boyfriend, artist Dickens Bascom, were in a clique of “glue artists” who would Bondo found objects to carousel horses, cars (one of which they drove), and toilet seats; she performed at the Renaissance Faire, and she would eventually write a rocking paen to the area’s generational ground zero: Berkeley’s Telegraph Avenue. Like Joni, Laura played the dulcimer; she was a friend of Joellen Lapidus, who’d made Joni’s instrument, and who was also at Joni’s house that day.

According to Estrella Berosini, the recitative phrasing (a departure from Joni’s earlier style) with which Joni would eventually record the songs of Blue sounded much like Laura Allan’s phrasing. “Take the first four bars of `California’: `Sittin’ in a park in Paris, France…’ to `…That was just a dream some of us had.’ The vocal phrasing over the strum on the dulcimer, the almost-talking style of lyric, the run-on sentences, the childlike detachment: they all couldn’t sound more like Laura. The lyric content is all Joni, but it was entirely Joni's version of Laura, and a stunning version. Joni's special brand of magic was so consummate that she could put on someone else's style as if it were a beautiful second hand dress, and it looked like it had been made just for her.”

In late July, Joni returned to Mariposa. The festival’s steely director Estelle Klein had also managed to lure James Taylor to the event. James was now a star, on the basis of his second album Sweet Baby, James and its hit single “Fire and Rain.” His manager Peter Asher had asked for $20,000, Taylor’s going fee. But Klein had crisply retorted: “$78 a day is what we’re paying.” Asher and Taylor had agreed to the token payment.

Joni Mitchell had met James Taylor briefly the year before, in Cambridge, but at Mariposa, now, they commenced a romance. Peter Asher, who was there with James, thought the pairing inevitable– and so did others. “I think they saw a lot of themselves in each other,” is how drummer Russ Kunkel puts it. “Both singer-songwriters, tall, handsome/ beautiful, soulful, and talented.” “It was no surprise” that they got together, says Danny Kortchmar, noting that when Joni and James were together “they were both painfully quiet, sensitive, encircling each other.”

*

Sheila is the author of eight well-received books, several of them NYT bestsellers, the best known of which is Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon -- And The Journey Of A Generation. She has written for (what the hell, let's use the vernacular) a ton of magazines, including Vanity Fair, New York, Glamour, the New Times Book Review, Styles and Opinion pages. She lives in Greenwich Village.