A History of Love

Marion Winik

Word Count 716

Since both my marriages are long over, thoughts of my wedding attire emerge draped in a veil of nostalgia, though in fact the pieces themselves are in my closet upstairs, were I inclined to pull them out and marvel that I ever fit into them.

I got engaged in 1984, at the age of 25, to a gay bartender and former professional ice skater I'd met at Mardi Gras the preceding year. (Yes, I knew he was gay, but we were madly in love and didn’t care. If you’d like further detail, I wrote a whole book about it.) The wedding was supposed to be in the spring of 1985 at the Hollywood Golf Club. This particular Hollywood was in suburban New Jersey; it was the club for golfing Jews in our area. Its entrance was across the street from the club for Gentiles, both founded in the days when anti-Semitism was unabashedly institutionalized. My mother was several times the ladies' club champion; we had a secret gate to the ninth hole in our backyard.

In January of 1985, my father had his second major heart attack, followed by a quadruple bypass. He was hospitalized on the Upper East Side of New York City, not far from where he worked. Terrified by this turn of events, I flew up from Austin to visit him. One day, my mother and I went out to lunch on Madison Avenue and passed a bridal shop with a handmade, ivory lace fantasia of a dress in the window. As butch a gal as I may have been, I fell head over heels for this extravaganza of femininity. My mother observed that it would certainly be ludicrously expensive, and she was right. It was $1500. But when I started wistfully rhapsodizing to my bedridden father about it, he commanded, in a sudden, impressive burst of his usual ebullience, "Buy it! Just buy it, Jane!" Jane pushed back, but Hy prevailed: this was a classic family dynamic. My father was a workaholic all his life; paying for things was his main way of showing affection. My mother was not stingy but was a much more conservative character in every way.

I had a fitting for the dress that very week, before flying back to Austin. The tea-length skirt would be lined with rose silk charmeuse. The lacy, beautifully fitted top would have Juliet sleeves (long, tight, with a puff at the top) and a collared illusion neckline through which you could see enough cleavage to prompt my grandmother to exclaim with delight, "She looks sexy!"

But that was over a year in the future. Though we were told 99% of bypass patients make a complete recovery from the procedure, my father was never really himself again. When he died in bed that March, my wedding was postponed. Instead family and friends gathered at the Bloomfield-Cooper Funeral Home. The dress was already on the way, the last thing my father ever bought me.

Not long after our eighth anniversary, my young husband joined my father wherever it is they all go. His death was an assisted suicide at the end of his long struggle with AIDS. At the time our boys were six and four. They were 11 and 9 when I remarried — this time, to a demonstrably heterosexual guy I met while on tour for my book about being a single mom. That wedding was held in the backyard of our new house in rural Pennsylvania, with 35 guests who helped us put on the wedding as a potluck with a talent show following. I wore a white lace bustier I bought on Burano, a island of lacemakers near Venice, with white satin Capri pants and a longish veil, and wrote up the whole thing for Oprah magazine. The articles about the decline and fall of the marriage were never published.

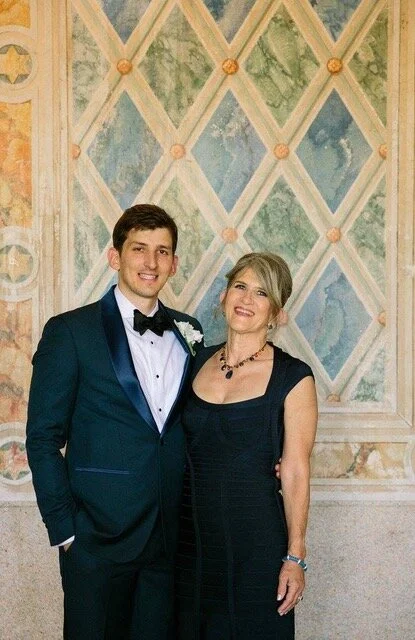

In any case, I think I looked as good as the almost-60-year-old mother of the groom four years ago as I did at either of these weddings. I wore a floor-length, navy blue Hervé Leger bandage dress I bought at TheOutnet.com, 10% off $724, worth every penny. And that, at least, still fits.

Marion is the author of First Comes Love, The Big Book of the Dead and many other books. Her award-winning column appears monthly at Baltimore Fishbowl and her essays have been published in The New York Times Magazine, The Sun, and elsewhere.